Keisha Hudson, Alexis Hoag-Fordjour, and Eve Primus

I have a hard conversation with our new attorneys. It’s really difficult when I tell them: “You can’t be effective.”

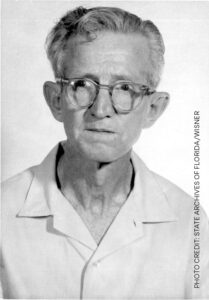

Clarence Earle Gideon

Sixty years ago, Clarence Earle Gideon wrote to the Supreme Court from prison: “The question is I did not get a fair trial. The question is very simple.”

A Florida court had denied Gideon’s request for a lawyer. In 1963, the Supreme Court ruled that, not only was Gideon entitled to a lawyer, so was any poor defendant facing prison time.

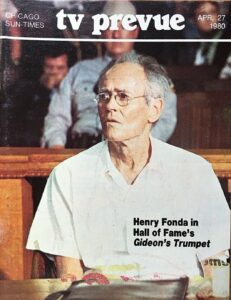

It was one of the most significant progressive victories to come out of the court. There is even a made-for-TV movie celebrating the decision.

Yet, as the legal scholar Paul Butler wrote ten years ago, “On every anniversary, liberals bemoan the state of indigent defense.”

As you’ll hear, on this 60th anniversary, there is still a lot to bemoan. The court created a new right—the right to counsel—but much of that right remains unrealized.

Yet as the harms of the criminal legal system come into sharper relief, there is a larger question: even if Gideon‘s promise was fulfilled, how much would that change who principally suffers under the current system: the poor and people of color?

Exploring Gideon’s legacy and silences on this episode of New Thinking are Keisha Hudson, the Chief Defender for the Defender Association of Philadelphia; Michigan Law’s Eve Primus, the director of MDefenders, which supports aspiring defenders at the law school; and Alexis Hoag-Fordjour, the co-director of Brooklyn Law’s Center for Criminal Justice and a former public defender.

The following is a transcript of the podcast:

Matt Watkins: Welcome to New Thinking from the Center for Justice Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins.

Sixty years ago, Clarence Earle Gideon wrote from prison to the Supreme Court: “The question is I did not get a fair trial. The question is very simple.”

A Florida court had denied Gideon’s request for a lawyer. In 1963, the Supreme Court ruled that, not only was Gideon entitled to a lawyer, so was any poor defendant facing prison time.

It was one of the most significant progressive victories to come out of the court. There’s even a made-for-TV movie, ‘Gideon’s Trumpet,’ starring Henry Fonda.

Yet, as the legal scholar Paul Butler wrote ten years ago, “On every anniversary, liberals bemoan the state of indigent defense.”

As you’re going to hear, on this 60th anniversary, there’s still a lot to bemoan! The court created a new right—the right to counsel—but much of that right remains unrealized.

The bemoaning, the advocating for fairness, they’re essential, but there’s also the larger question of: even if Gideon’s promise was fully realized, how much would that change who principally suffers under the current system: that is, the poor, people of color?

And how much can defenders do to change that—both inside the courtroom, but perhaps more critically outside of it?

To explore this, we have an all-star panel.

Keisha Hudson heads up the Defender Association of Philadelphia. She has a long history of leadership and advocacy in this field. In fact, she was fired from her previous job after speaking out about the county’s bail practices.

Michigan Law’s Eve Primus is a former public defender. She’s also the founder and director of MDefenders, an organization that supports aspiring defenders at the law school.

And Brooklyn Law’s Alexis Hoag-Fordjour is the co-director of its Center for Criminal Justice and spent more than a decade as a lawyer with both the NAACP and with the Office of the Federal Public Defender in Nashville.

I started the conversation by asking: what was truly landmark about the Gideon decision? Keisha Hudson speaks first, followed by Alexis Hoag-Fordjour.

Keisha HUDSON: We’ve been around since 1934. And so, I like to say we were Gideon before there was Gideon, and many incredible advocates were Gideon before there was Gideon.

But it was really critical that the Supreme Court said that if you are indigent, if you cannot afford it, a counsel will be appointed to you. It was a landmark decision—in that era, a series of landmark decisions—giving access to justice for those who could not access it before or a meaningful access to justice.

Unfortunately, what has happened since—Alexis and Eve, interested in your perspective here—is how following Supreme Court decisions have completely lowered the bar on what that access to counsel means and really setting the lowest of bars in terms of funding and resources and training and access to experts.

Gideon, while remarkable, the Supreme Court in several ensuing cases said, “You don’t get much of a lawyer,” or “your lawyer can be the best and most zealous advocate, but they’re not going to get much of anything to help them prepare for or litigate or advance your case.”

And so, while there was a promise of Gideon, it in my opinion, has not been realized as we approach the 60th anniversary.

Alexis HOAG-FORDJOUR: In terms of the landmark nature, the fact that you had an individual that was facing jail time, prison time, if he was convicted—Clarence Gideon—and the fact that he didn’t have defense counsel facing these awesome resources from the government, from the state of Florida, it was a big deal that the Supreme Court said people who are indigent, people that are too poor to afford their own lawyer must be appointed one by the state.

And as Keisha mentioned, there were a number of states, California and New York, that were providing counsel to people who were facing criminal charges that were too poor to hire their own lawyer. But there were still a handful of states—largely, not coincidentally in the South—that were not providing lawyers.

And there are still counties, I know Eve has done a lot of work on this, in more rural parts of states, even in New York State, even in California, where access to public defenders doesn’t look the same as it does in a large municipality.

And so, Gideon had this, in many ways, aspirational language, this aspirational promise that has not yet been actualized because the resources that are provided to states to cover indigent defense are not equal. They definitely don’t match the resources that state prosecutors have. And so that’s where we’re seeing the disparity.

WATKINS: Eve, what are the limits of right of counsel? Who gets it—I suppose, both in that original ’63 decision, and then how that has changed subsequently, and then if you like, how the reality actually plays out on the ground, because just because we pass a law does not mean the reality changes overnight, or even 60 years later?

Eve PRIMUS: The most remarkable thing to me about the Gideon decision was the recognition about how essential the assistance of counsel is for the fairness of a trial, because it’s a recognition of how complicated our system is, of how much expertise is required, of how much preparation needs to go into these cases.

I think the unfortunate thing that has happened both in subsequent Supreme Court cases and on the ground is that has not panned out in the reality of what exists.

At the Supreme Court level, they cut back substantially on the right for… People who are charged with felonies can have a lawyer. But if you’re charged with a misdemeanor, it’s only if it results in actual imprisonment that you’re entitled to a lawyer under the Sixth Amendment.

WATKINS: Even then, that’s not always being observed, right?

PRIMUS: Right. And that’s violated constantly: reports after reports of individuals who are charged with misdemeanor offenses going into court and being forced to essentially represent themselves. These are invisible to a lot of appellate courts, even though the actual consequences for people being convicted of these misdemeanor offenses are huge.

They can lose their right to vote. They can lose their ability to stay in this country. They can lose their access to housing and benefits. They can lose the ability to get jobs and the stigma associated with it. That’s to say nothing of the problems that Keisha has already mentioned about the fact that Gideon has always been an unfunded mandate.

The Supreme Court said, “This right exists.” But they never said who’s going to pay for it or at what level this right should be provided. And so, it’s not shocking that a lot of states, a lot of them pass the buck to the localities.

And these counties are cash-strapped. It’s never politically popular to do things that support people who are accused of criminal offenses. You get accused of being soft on crime. And so, it’s not shocking that the reality of putting this into a political system is we’ve got a lot of systems where they don’t use public defenders at all who are full-time employees.

They just put it out to a low-bid contract: whoever bids on a contract to represent indigent defendants and is willing to do it for the cheapest amount will be the person who gets this contract. And they don’t provide them with resources for investigation. They don’t provide them with resources for expert witnesses. And in fact, the financial incentives, it’s just a system that is set up to make this a fast processing of poor people of color into prison and jail.

WATKINS: It seems like, what is the incentive for the state to provide proper funding for public defense, given the history of racism and the notions of undeserving poor in this country? And Gideon did nothing to address this problem of, “Why would the state want to provide money for a robust defense?”

HOAG-FORDJOUR: There’s always been stigma attached to people that receive public services and, particularly, Black people who received public services. And it was no coincidence that Clarence Gideon was a white man, and this was the case that went before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1963 where they made this grand proclamation.

And then just two decades later—Strickland versus Washington, which the court decided in 1984—we have the least compelling of defendants who has pleaded guilty to three murders and additional crimes.

And then this is the case that the U.S. Supreme Court decides, “Okay, well, if you have the right to counsel, you must also have the right to effective counsel.” And they establish this standard. And when I teach this case to my students in criminal procedure adjudication, their takeaway is, “Oh, you’re basically guaranteed a mediocre lawyer. And even if your lawyer is not that mediocre, it might still be okay.”

HUDSON: And you have to show prejudice.

HOAG-FORDJOUR: Exactly.

HUDSON: You have to establish it.

WATKINS: Right. If the court thinks you were guilty anyway, it doesn’t matter how bad or even racist your attorney was, right?

HOAG-FORDJOUR: Justice Marshall, in his dissent, he was basically like, “Prejudice shouldn’t be required because all people, all indigent people, everyone accused of crime deserves quality representation. And it shouldn’t hinge on the fact that you might be able to make out that you should have been acquitted but for your lawyer’s deficient performance.”

And we see so many cases in which someone has engaged in criminal conduct, but yet their lawyer was asleep, was drunk, was explicitly racist! And yet, the court is not finding that that impacted, in some way, representation to the level that it violated the Sixth Amendment.

PRIMUS: I will say also, I think there’s a real tension between Strickland and Gideon. Gideon recognizes that there cannot be a fair process with a reliable outcome if you don’t have meaningful assistance from a lawyer.

So, this idea that you have to show prejudice to the outcome in Strickland, it’s like, “Okay, you’ve shown us you didn’t have a good lawyer, that your lawyer was deficient, and that’s not enough! You also have to show it would’ve mattered to the outcome of your case.”

And the problem is, if we care about fair process, it should be enough that the process was unfair, that you did not have a competent lawyer. So, the prejudice inquiry really just cuts a lot of these claims out and leaves people with convictions that are known to be based on deficient, poor performance by their lawyer. That’s, I feel like, a stain on the way in which our system operates.

HUDSON: And as someone who did capital appellate work for 10 years, literal death consequences, having represented people who are on death row in Pennsylvania, and we had cases across the country where every deplorable behavior by counsel at the time of trial didn’t change the outcome, and people have been executed.

I wanted to also throw “chronic” into the conversation in terms of this whole…

WATKINS: Sure, it’s time, I think!

HUDSON: …about critical stage, which infuriates me, because having worked in a county, in Montgomery County, where a preliminary arraignment where you are going to find out the charges where bail is going to be set, literally determining whether you’re going to spend your time before trial in a jail cell, in a cage, or you’re going to be able to be at home.

And we all know the outcomes are better and the collateral consequences are so much less when you are home and in the community.

WATKINS: It’s that very consequential first touch, the arraignment.

HUDSON: Very consequential stage, and in places like Montgomery County and the majority of counties in Pennsylvania, you don’t get counsel at that stage. It is the police officer, and it is a judge, and it’s a district attorney.

You are standing there in this critical, what I would term probably one of the most important stages of your case, and you have no counsel or access to counsel. And the court’s saying that you don’t get a right to counsel.

In juvenile summary proceedings—“it’s just a summary, it’s just a fine”—except we see a huge burden on not just youth, but their families who are not going to be able to pay these astronomical fines. But again, you don’t get an advocate because that’s just not important enough.

And so again, the Supreme Court in so many cases, just whittling down what was this huge promise in Gideon to less than nothing.

WATKINS: And then I do think we ought to talk about caseloads a little bit. That’s a well-known problem, but that’s where we see the funding issue really playing out. Alexis, maybe, do you just want to give listeners a quick sense of what public defenders are actually juggling on the regular? I saw one public defender saying, “We’re not practicing justice, we’re practicing triage.”

HOAG-FORDJOUR: Exactly. That’s a perfect term to use, is triage. And in my research of public defenders, doing qualitative research with folks in, say, East Baton Rouge, in Louisiana, I talked to a young woman there who had 190 felony cases. She said she, sometimes, met with a client for the first time on the day the trial was scheduled, that there was one investigator for her entire office.

That meant that out of her cases, an investigator was often not part of the process and literally just processing cases with that kind of setup. And even in jurisdictions where there are more resources… I spent an early summer in law school at the Bronx Defenders, a supervising attorney there who was training junior attorneys, training summer interns, had over a hundred cases.

And we literally ran from courtroom to courtroom in between appearances. And this was sort of the day in the life of a public defender at a relatively well-resourced office.

Like Keisha, I represented people who had been sentenced to death in appeals, but in the state of Tennessee. Even in a capital case where death is a potential outcome, lawyers there—and you had to have two lawyers representing each individual—and the second chair lawyer in one of my client’s cases met with a client for the very first time on the first day of trial.

And this was the lawyer that, given the division of labor, was solely in charge of making the case for life in the sentencing phase of trial, not even knowing a single detail about this person’s life, never having interacted with this person, but yet was supposed to convince a jury to spare this person the death penalty.

So, it’s across the board. Regardless of resources, you have public defenders that are expected to juggle far too many cases that is possible for them to do a sufficient job on any individual case.

HUDSON: I have a hard conversation that I have with our new attorneys. It’s really difficult for them to hear when I tell them that you can’t be effective. “I’m going to train you,” and we have excellent training here at the Defender Association and we are lucky to be able to do that because most offices in Pennsylvania don’t have that capability or the resources to train. There’s zero training!

But just to explain to them that, “If you think having 40 cases means that you’re going to go into court and do everything you need to do for 40 human beings, it is impossible. And though we are training you, and we have the resources that we can assign to you, your caseloads are untenable.”

No one likes the word “triage” but part of the training is how you manage that caseload: how you assess a case, how you are accounting for biases that may come in, because that plays a role in terms of, “Who am I viewing is the case where I’m going to really prep and file the motions, or the case that I’m going to assume he’s guilty, and he did it, and I’m not going to do all the things I need to do?”

But how do you manage and prepare as well as you can for a 40 or 50 or 60 caseload list? You can’t.

WATKINS: Gideon had its own Cold War context, just like the Brown v. Board decision, in which we didn’t want it to appear like the individual is appearing unprotected against the immense power of the state.

But along with the funding and the caseload issues, you have this immense mismatch between the power of the defender and the power of the prosecutor. Again, that’s something Gideon is silent on entirely and did nothing to address, and the Supreme Court has only ratcheted up in the years since—this mismatch, right?

HUDSON: Is a prosecutor there to seek justice, or obfuscate, or put up a barrier to justice? In my 20 years as a defender, too many and countless examples in both capital and non-capital cases where the role of the prosecutor is to obfuscate and to delay justice.

And so, what are the mechanisms to really tether them to a fair practice? A lot of these issues, again, Gideon didn’t speak to, cases since haven’t spoken to and/or they’ve restrained.

PRIMUS: There’s a way you can look at what the Supreme Court has done here as undercutting the defense function, not just in not giving protection or resources to or stature to the defense attorney’s existence, but also giving power to the prosecution in setting the system up in a way that hides these problems.

For example, like Keisha mentioned earlier, that you have all of these stages where people’s freedom, that first touch, where their freedom is at stake, and there are no lawyers there. And then you have these prosecutors, often, at those stages making plea deals that essentially say, “If you admit to guilt, you can go home right now. Otherwise, we’re going to hold you.”

And the pressure on individuals is immense. Even if they get a lawyer at that stage, which they are constitutionally entitled to if they’re facing imprisonment—because a plea deal is a critical stage—even if they have a lawyer then, the lawyer hasn’t had time to investigate and figure out what’s going on.

It’s the first moment. And so, the prosecutor says, “Either you can take this, admit guilt and go home, or you’re stuck in a cage for weeks or months.”

And we have data that innocent people opt to plead to get out. And so, the Supreme Court doesn’t regulate that process at all. The Supreme Court has made affirmative decisions saying, “We are not going to regulate prosecutorial plea bargaining. We’re not going to regulate the kinds of offers that they can make. We’re not going to look at their motivations for why they’re making these offers.”

And then things like prosecutorial misconduct or like ineffective assistance of counsel are things that are not clear because it’s all hidden outside of what happens in the courtroom.

WATKINS: Which is very much not the ideal of Gideon or the public understanding of Gideon that’s about this fair trial, and to go back to Henry Fonda not having to defend himself in the Florida courtroom, in fact, we have 95 percent of cases ending in this black-box-plea-bargaining way, which really undermines any sense of the promise of Gideon, I would think.

HOAG-FORDJOUR: Well, I think it’s so critical, too, that the public has a better understanding of the injustice—the chronic, pervasive injustice—that exists on a daily basis across this country. I think about some of the podcasts that have come out to talk about the daily injustice—whether it’s Serial, the series of podcasts that talks about wrongful convictions.

And it’s such a critical turning point. When I think about my own indoctrination of what the justice system was in the ’80s and ’90s, and Cops was pervasive, and Law & Order, “There are two sides to every story: the prosecution and the police.” And it’s like, “That’s actually the same side.”

HUDSON: And no mention of a public defense!

HOAG-FORDJOUR: Exactly!

HUDSON: We don’t even get mentioned at all!

HOAG-FORDJOUR: Exactly. And so, it’s been really critical that the public has a better understanding of what happens. And as I think about the power potentially that voters have to push their lawmakers to actually fund public defense.

Some of the lawsuits that are happening all over the country, Keisha knows this intimately, but demanding equal funding for indigent defense, demanding equal funding for people who are facing criminal charges, because it’s not sustainable. And this very fear that the Supreme Court talked about, which Eve has highlighted in Gideon, continues to exist when this idea of public defense isn’t adequately funded.

WATKINS: Now, something I’d like to do, though, is to try to take this conversation beyond just the four corners of the courtroom—which as we’re discovering, doesn’t exist so much in reality—and ask: even if all of the silences in Gideon were addressed—and we’ve gone through some of them, not all of them—how much could better defense lawyers actually solve about this crisis of mass criminalization and incarceration?

Is there a danger at some point of overestimating how much better representation could actually do?

PRIMUS: Honestly, I’m going to say no. I think people don’t understand how important the defense function is. We talk about criminal legal system reform, and everybody talks about, “We need progressive prosecutors,” or, “We need more defender judges on the bench,” or, “We need bail reform.”

And the people who often get left out of that conversation are the public defenders. There is one role in the Constitution that is set out and designed to be the advocate for those who are brought into these courtrooms and charged with crimes, and that is the defender.

And what we have seen is well-organized defender agencies can have an immense impact on not only what happens in the courtroom, but what happens outside of the courtroom. They can lobby to ensure that unjust laws do not get passed that over-criminalize and target Black and brown poor populations. They can engage in community outreach that brings to the attention of legislatures the problems with locating jails and prisons incredibly far away from community members that inhibit visitation, that prevent reentry.

I don’t think we know if it would be enough because we’ve never actually given defender agencies their due and their chance, and the ability to do what I think they can and should be able to do.

HUDSON: Pennsylvania is one of two states where the state legislature does not provide any funding to public defense. And so, we have 67 counties here, and so, justice is not only zip code by zip code, it’s county by county.

Last week, Governor Shapiro in his first budget address, proposed that we take ourselves out of that statistic and proposed state funding in the amount of $10-million statewide. Ten million is woefully, woefully inadequate, but it is an acknowledgement. And there were some strong words from him about the importance of public defense and the importance of funding.

And so, $10 million is the starting, but I can’t envision a world where we get to the point where the public defense function is going to be well respected. I think often about the people we represent and what society as a whole thinks about the people we represent, who are poor, in a lot of urban centers are brown and Black.

We’ve never prioritized and wanted to understand or uplift people in poverty. And in fact, it’s been the opposite. It’s been by design. Whether it’s where we decided what districts are redlined or neighborhoods are redlined, or where we’re going to put the highway, it’s almost this otherization of those people. And we represent *those people.

No one has had the political courage to say, “We are going to make this incredibly well-funded and well-resourced function, this constitutional right that you get.” There’s never been that conviction or courage to do that.

I have to throw independence into the conversation—again, as someone who was fired for advocating—that the understanding why the defense function needs to be not only well funded in research, but independent, again, we have not seen the political will to do that and ensure that.

HOAG-FORDJOUR: When I look about, “What could adequate funding be like?” I think about the federal system. The federal defenders are funded through the federal judiciary. And in terms of federal defender salaries, the resources of investigators, the ability to hire experts, you have something that looks a little bit closer to parity.

And even still, when we look at that system, the threat of incarceration and the gravity of the sentences, the length of the sentences, tends to be even higher.

We’ve already talked about this idea that in state court about 95 percent of cases end in plea deals. It’s an even higher number. I think it’s like 97 percent in federal court. So, even with equal resources, the sentencing, the consequences, are so severe that few people are willing to risk going to trial and potentially facing even lengthier or more serious consequences.

So, I guess that even with equal resources, the other mechanisms and levers in the criminal legal system and the adjudication process are stacked so severely against people facing charges and in those who are convicted.

HUDSON: The trial penalty is one of the most infuriating aspects of this system, that a prosecutor can make my client what is an appealing offer, and the client says, “Oh, actually I’m going to go to trial.” And the prosecutor will then say, “Oh, this deal is going to evaporate.”

Which is a technique they use: “So, decide quickly because it’s just going to keep going up.” Again, how we’ve just armed the prosecutors to wield and, I think, abuse that power. And then if you go to trial and the judge is well aware that you had a plea offer that you rejected, then you’re going to be sentenced to periods of incarceration well exceeding that initial offer.

Our clients know this. By the time they get to the bar of the courts, even if they were ready for trial, even if there are good issues to argue, and there are really good arguments to make, and the case laws on our side, oftentimes, my clients are making that in-the-moment decision, having watched me and/or a judge for five hours before they get to come up to the bar of the court.

So, the system is, I think, designed, again, to dissuade anyone from exercising that constitutional right.

HOAG-FORDJOUR: One of the starkest examples of that trial tax is people facing the death penalty. I represented multiple people who were offered a life sentence, something short of death, decided to go to trial, and then were sentenced to death.

And this idea that they’re being sentenced to death because they’re the worst of the worst, while pretrial, the prosecution was willing to offer them a life term or even a term of years. And so, I just want to underscore Keisha’s point there that, again, aspirationally, each person accused of a crime has the right to a trial, but it’s so rarely exercised.

WATKINS: Alexis, as a student of Derrick Bell’s, I’m wondering, do you have thoughts about, not just the role of public defenders, I guess, but again, how much we should be turning to look to the law to be an ally of progress, particularly racial progress?

HOAG-FORDJOUR: As a student of Derrick Bell, he had so many powerful theories. And he remarked on the permanence of racism. But this idea that this tweak, the tweaks that we do around the law, even the Civil Rights movement and Civil Rights legislation, how it can provide sort of a temporary peak of progress, and then eventually, we slide back into the reality of subordination and racism.

But this idea that somehow using the law as a tool can fix what’s wrong with public defense? In *part, but I think the power is really with individuals that are directly impacted by this system and the ability to use their voice and use their platform and use the power of mass demonstration and protests to effect change. It has to happen at the same time.

I think these sort of conversations and this awareness exist and are flourishing in law schools. And my students are not content just to work within the system. They want to learn the skills and the tools to take the system completely down and replace it with something else. And they are so far ahead of where I am in my own thinking, but I am continually inspired by them.

I know some of my students are working for Keisha right now, but they have these really big ideas that I think are beyond my own awareness and imagination when I think about myself as a law student 15-plus years ago in school. But there are so many different avenues for change, and the law is not the only one.

HUDSON: It absolutely is not. One of the things that we prioritize here, it’s one of our core values, it’s really working in the community and being present in the community. Our team here just put together a documentary called 57 Blocks. And 57 blocks are where 10 or more shootings happened on that block.

And when we look at those 57 blocks and go back and think through the fact that 52 of them were redlined in the ’30s, and now, we are here in 2023, is it no wonder after such grave disinvestment that we’re seeing crime and violence in these predominantly African-American neighborhoods?

So, being able to go out in the community, know where our clients live and work, and what they experience, and talk to them, but then find ways to engage them through participatory defense—and we have eight hubs here.

And it’s a new group of public defenders coming into the work. I have to say. Alexis and I, when we were in law school, the fact that the young Black female public defenders, week one and week two, were coming back from court and saying, “The judge said this or acted in this way.” I would’ve shrugged that off because it was just the expectation as a public defender that you’re going to get abuse.

And for us now, having a hard conversation to say, “Actually, we have some power. Attorneys are not going to be treated that way, or investigators, whoever’s in that courtroom or that space, we are doing incredible hard work every single day, and we deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.”

And it’s fantastic. That’s progress.

WATKINS: To bring this back to Gideon, is the goal in some ways, then, for defenders to work to make the formal rights enunciated in Gideon—work to make Gideon‘s promise an actual reality on the ground? But then there’s both-and larger goal of, “How do we work to just reduce the system, reduce the harms of that system, overall?”

But can that both-end be done by defenders? You’re saying it is, Keisha, which I completely respect. But obviously, there’s huge structural constraints everybody’s laboring under.

HOAG-FORDJOUR: Yes-and!

HUDSON: Yes-and! It cannot be done solely by defenders. It’s in the partnerships that we have to continue to foster and sustain. But it is in pushing the conversation on independence and insisting on equal funding, on parity between us and the district attorney’s office.

But we, as a country, have to take a hard look at how we have by design continued to disinvest in communities of color and structural inequities that have just continued to perpetuate, that push people into the system.

My clients will always be coming through our doors. When I look at who they are and where they’ve come from and what has led them to the criminal justice system, it is always just a story of poverty and/or trauma, and/or living in a community of violence and not having enough.

I would love for us, as a country, to take a really hard look in those social institutions and to fund them, and resource them. Until then, you need to fund and support public defenders. But we need to have a hard inward conversation.

PRIMUS: I think in a lot of well-funded or well-structured public defender offices, you have positions within the public defender office that are designed to not only address individual representation, but more systemic change.

A number of public defenders’ offices have these individuals who their purpose or their goal is to look at how the system is working with respect to all of the clients who are coming through and find problems in the way that the system is functioning, and think with the chief defenders in those areas about steps to take to go forward to try and bring about change.

What does that look like? Sometimes, it looks like policies in the defender office that say, “We’re all going to start to make these demands because this is a problem that we’re going to focus on, and we want to start to create a paper record to set up arguments to our counterparts, whether it’s going to be in a political vein or a legal vein down the line, to try and bring about reform.”

And there have been real opportunities and real ways in which defenders have been able to push for change in the way the system operates.

Zealous is an organization that talks about how public defenders can do advocacy outside of the courtroom and leverage media to try and present a different public image. And that affects policymakers.

So, I think there’s lots of examples around the country of different ways that an organized defense function can think about strategic moves going forward, if you can get them out of the basic triage mode that the underfunding causes in so many places.

HUDSON: I’m glad Eve brought up Zealous. We recently partnered with them and looking at how we do our training to teach storytelling and be better storytellers in the courtroom and in our mitigation and sentencing advocacy. But also, “How can we harness the power of those stories,” which I’d rather be talking about, and working with groups like Zealous, really being able to take that power that we have.

We’re the only ones who hear our client’s stories, because they trust us, and we have the umbrella of attorney-client privilege. We’re the only ones who know it and should be telling it, to advance interest, including legislation that’s going to harm them. And so yes, the storytelling remains critical.

HOAG-FORDJOUR: The solution to harm and the solution to crime isn’t to prosecute people more, and then once you’re prosecuting people more, provide them adequate funding for public defense, and then incarcerate them for these lengthy sentences. I think for the first time, the country is starting to have a really hard critical look on the lack of effectiveness of that tool—the whole criminal adjudication system to address crime, to address harm.

Keisha’s already talked on some of these themes with this idea that we know as a society what reduces criminal conduct, which is to fund the basic needs and services of people: to allow for adequate housing, living wage jobs, people having connection to community and accountability, access to education.

These are the measures that can reduce crime from occurring. And so instead of funding more law enforcement, instead of funding prosecutors’ offices, this idea that we can reroute some of this funding in other places, and that will actually work to reduce crime. And yes, we still need to fund public defender offices more–

HUDSON: Yes-and!

HOAG-FORDJOUR: …and give them more resources, yes.

HUDSON: Going back to what you said, yes-and.

WATKINS: That feels like a good place to end what I hope was a forward-looking conversation. And let me flag that this is the first in a planned three-part series on the legacy of the Gideon decision and the state and future of public defending.

On today’s episode you heard from Eve Primus, the Yale Kamisar Collegiate Professor of Law at Michigan Law; Alexis Hoag-Fordjour, an Assistant Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Center for Criminal Justice at Brooklyn Law School; and Keisha Hudson, the Chief Defender of the Defender Association of Philadelphia. For more information about this episode, click the link in your show notes, or go to innovatingjustice.org/newthinking.

For their help with this episode, thanks first to Arnold Ventures, for their support of the Center for Justice Innovation’s Gideon at 60 project. My thanks as well to Vincent Southerland at New York University’s Center on Race, Inequality, and the Law, for the conversations we had that helped to shape what you heard today. Thanks also to my colleagues Lisa Vavonese and Alysha Hall, and to the Brennan Center’s L.B. Eisen.

This episode was produced by Julian Adler and myself and was edited by me. Samiha Amin Meah is our director of design, Emma Dayton is our V-P of outreach, and our music is by Michael Aharon at quivernyc.com. This has been New Thinking from the Center for Justice Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins. Thanks for listening.