-

Matt Watkins

Matt Watkins

-

Ross Joy

Housing Court in most places does not resemble anything that most people imagine court being.

Long-time resident Andrea McKnight (left) with housing team members Ross Joy and Shamar McCall

The pandemic has exposed and deepened America’s housing crisis: the lack of safe and affordable housing; the iron grip of how that shortage plays out by race; and the connections among evictions, public health outcomes, homelessness, and criminal legal involvement.

There are pockets of innovation across the country: new approaches to Housing Court—where critics charge due process rarely exists for tenants; and new on-the-ground efforts to prevent evictions before they reach court. Lessons have been learned during the pandemic, but will they be listened to?

Housing team member Marissa Williams: “I love what I do here.”

One of those pockets of innovation is in Red Hook, a mostly segregated neighborhood near Brooklyn’s waterfront. The Red Hook Community Justice Center, a project of the Center for Justice Innovation, adopts a housing-first justice approach—the recognition that housing is a human right, a linchpin for human thriving and community safety.

What if more jurisdictions, more court systems across the country, supported similar work?

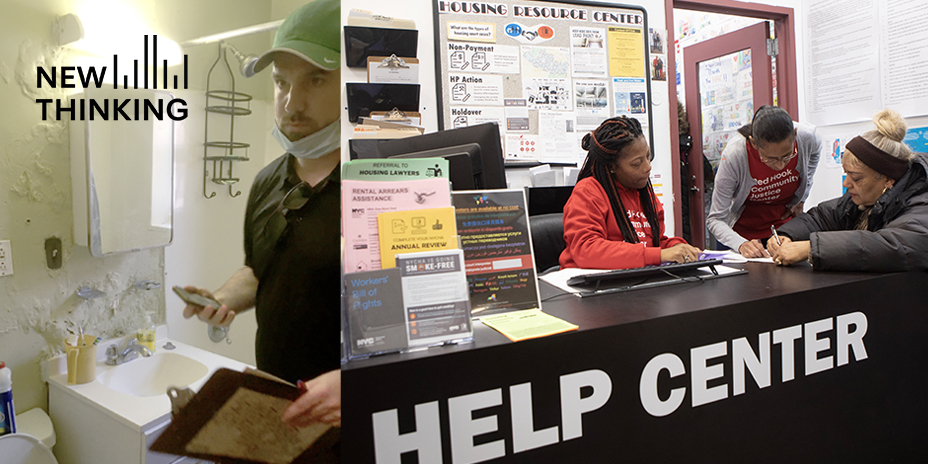

Water damage behind the walls of an apartment visited by Red Hook’s housing team

On this special episode of New Thinking, hear a profile of Red Hook’s housing team, helping residents of one of New York City’s largest public housing developments navigate housing court, and working in the community to document needed repairs and ensure tenants get the support they need to avoid evictions coming to court in the first place.

The following is a transcript of the podcast:

Shamus ROLLER: My thing about evictions is it’s a moment of crisis for a family and that if you can intervene, and intervention is really not that expensive in comparison to the downstream costs of this, it just is that moment in which it just makes so much sense to intervene from a societal perspective.

Matt WATKINS: Welcome to New Thinking from the Center for Court Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins. That voice you just heard belongs to Shamus Roller. He’s the executive director of the National Housing Law Project. The pandemic has exposed and deepened America’s housing crisis: the lack of safe and affordable housing; the iron grip of how that shortage plays out by race; and then the connections among evictions, public health, homelessness, and criminal legal involvement.

There are pockets of innovation across the country: new approaches to Housing Court—a broken system in most jurisdictions; and new on-the-ground efforts to support tenants, to prevent evictions before they reach court. Lessons have been learned during the pandemic, but will they be listened to?

One of those pockets of innovation is in Red Hook, a mostly segregated neighborhood near Brooklyn’s waterfront. A pier features a great view of the Statue of Liberty. The Red Hook Community Justice Center, a project of the Center for Court Innovation, adopts what we could call a housing-first justice approach—the recognition that housing is a human right, a linchpin for human thriving and community safety.

What if more jurisdictions, more court systems across the country, supported similar work?

Let’s keep that national picture in mind, then, as we listen to this portrait: Evicting Evictions.

Ross JOY (on phone): Oh, ok, there are some residents below you on the C-line reporting a water leak issue that it seems like NYCHA hasn’t been able to fix…”

WATKINS: This is Ross Joy, trying to track down the source of a leak.

JOY: It seems pretty bad… a pipe that’s broken inside the wall.

WATKINS: Ross is part of the housing team at the Red Hook Community Justice Center.

The Justice Center has a Housing Court that works exclusively with a complex called the Red Hook Houses. The Houses are one of New York City’s largest public housing developments. They’re almost a city unto themselves: 28 buildings called home by about 3,000 tenant families.

Today Ross is calling about one family’s apartment Its walls are bubbling out from water damage.

The neighbor above Ross has reached isn’t having a leak problem, but she says the lights are out in the public hallway and no one has come to fix it.

Ross asks her to send him a photo of how dark the hallway is at night. And then he logs on and files a ticket with the housing authority.

Ross is part of a housing court team whose job is to keep people in their houses. And to make sure they can access a process that honors tenants’ rights.

JOY: The work of preventing eviction I think is very strongly aligned with my values that communities should be stable, where people can live and thrive.

WATKINS: New York’s public housing authority estimates it would cost $40 billion to clear its backlog of repairs. Along with an affront to dignity, repairs that don’t get done can be a health hazard: your gas or your heating is out, untreated mold in your walls, lead paint that isn’t replaced. But they can also lead to evictions: people withhold their rent, but if they don’t document everything, they can end up with a rent bill they can’t meet. Ross moved to New York six years ago, after working to organize tenants on the south side of Minneapolis.

JOY: A lot of our justice work I think about as economic justice, and that’s who rents is folks that don’t have the means, that don’t have the assets. And it’s not they don’t have the ability to, but it’s the hand that they were given. And I think too often we allow, especially in the rental market, for corners to be cut. And so, it’s making sure that there’s fairness at the bottom level, so folks can grow and be awesome and have their own independent lives, and not have to deal with the same problems, the same notices from their landlord that are confusing, the same repairs that don’t get done.

WATKINS: I also want to introduce you to Ross’s colleague, Marissa Williams. Marissa’s often at the help desk of the housing resource center. She guides people through the bureaucracies of both the public housing authority and housing court; think filing your taxes, but more paperwork. But Marissa’s also out in the community, looking for problems to solve before they grow. And that’s easier for her to do because she grew up the Red Hook Houses.

Marissa WILLIAMS: And then being that I lived out here all my life, and I know everybody out here, it was a win-win for the community. I can serve my community and still work here and do something that I love. It pushes me every day to help back and get back to my community. And my family’s still out here, my friends, and I see what they go through on a day-to-day basis, I see what my grandmother go through.

As long as I’m here, they’re going to receive help, and when I’m not at work, I’m at work because they could see me in the supermarket and still, “Hey Marissa, my repairs wasn’t done. Or do you know anybody that can help me get out of here or do a transfer request?” And being that I know that I could tell them to come in, come see me or come see the staff. It’s excellent staff here. So, they’re very happy that I’m here and I’m happy that I’m here. I love what I do here.

WATKINS: Shamus Roller with the National Housing Law Project says eviction rates in many cities have returned to the high levels they were at before the pandemic. Evictions can be disastrous for families, and the brunt is not borne equally. Some experts say, what mass incarceration has done to Black men, evictions are doing to Black women. Roller says intervening early is essential.

ROLLER: We knew for a long time that evictions have significant downstream consequences: worse health outcomes, job loss, homelessness in the worst cases. But oftentimes the step before that is some sort of overcrowded conditions in which people are living in. Suicide rates increase.

And then during the pandemic, what we found is that people who were evicted, that the numbers in those communities have produced much higher rates of COVID infection and COVID death as a result. What we captured in the pandemic was this crucible of why evictions can be bad for a family from economics to health, but also that it showed us why we need to intervene in that process.

My thing about evictions is it’s a moment of crisis for a family and that if you can intervene, and intervention is really not that expensive in comparison to the downstream costs of this. Oftentimes an eviction can be solved for a couple thousand dollars. It just is that moment in which it just makes so much sense to intervene from a societal perspective.

SOUND/Shamar MCCALL: This building right here, on the other side? You can’t even get to it the regular way! You gotta go through the projects, go through a bunch of cuts. That’s what it is out here now.

WATKINS: We’ve left the Justice Center now. Ross and Shamar McCall, a younger member of the housing team whose voice you just heard, are on their way to check out that leak Ross was calling about. But Shamar is talking about the construction that’s taken over the Red Hook Houses.

Every building is surrounded by chain-link fencing, and to get most places, you move through narrow fenced-in corridors and a lot of scaffolding. It’s easy to lose your way. And on the other side of most of the fences is a mess: loose construction materials and piles of garbage bags are everywhere.

Andrea MCKNIGHT: It’s really backwards, ass-backwards…

WATKINS: We’ve just bumped into a long-time resident of the Houses, Andrea McKnight. She’s out walking her dog, Diamond. The construction that’s upended the Houses is meant to prevent a repeat of the flooding damage caused by Hurricane Sandy. But that was ten years ago. And now that the work is finally underway, it’s happening throughout the entire blocks-long complex. To McKnight, there’s no end in sight.

MCKNIGHT Q & A: But it just seems like there’s not enough workers! Watkins: Like no one thinks it’s very urgent. McKnight: Exactly! And I’ll say this: if it was a difference in the ethnicity that would be here, it would have been done faster, it would have been done differently. And I’m saying that because it’s true. If it was an all-white, Caucasian neighborhood… It’s not even an easy thought.

WATKINS: It’s close to noon on a very hot spring day. McKnight points through the fencing to a neighbor’s first-floor window. Just below it are piles of construction debris.

MCKNIGHT: Because look at the stuff that’s there. That person on the first floor? He’s an elderly man. His air conditioner is not even working full force now because of the dust and stuff that’s… You know what I’m saying? It’s… I’m done.

SOUND UP/WILLIAMS: They’re not being heard, people could be like, “I hear you, but are you listening to what I’m really going through?”

WATKINS: Growing up in the Houses and now working to help keep residents in their apartments, that feeling of, “I’m done,” is one Marissa Williams has heard before. She says it’s where a lot of her conversations start at the housing help desk.

WILLIAMS: Because sometimes it don’t be the repair issues or the annuals that need to be done, or a job, they’re just mentally drained from going through all of this and not understanding, and not having somebody that can help them or them not understanding how to do their lease by themselves.

So, once we start talking to them and then we could reach out to their housing assistant to figure out what they really need, that’s how we can put everything together. And it’s all a matter of listening. Some tenants just come in here just to talk, or they’re going through something at home, and they’re embarrassed to say it.

Once they start talking to me, my mind start going, “Hey, I could reach out to this person over here, downstairs in Youth and Community to get you some clothes, Victim Services, I could get you some diapers or some formula.”

And that’s the only thing I really… I have to listen, because I live out here. I know what it’s like. I know what it’s like to be looked down on because of where I’m from. And then when I open my mouth and I start talking and I tell them where I work at and what I do, they be like, “Oh, so you actually do know what you’re talking about?”

Yes, I do. Just because I’m from Red Hook and you think that’s the projects. I call it my community. I learned that from being in the Justice Center. I’m not in a project no more, I’m in a community. And we’re going to build our community and make it the best one possible.

WATKINS: There’s listening, there’s being present, and there’s providing people with the early resources and support they need. There’s also introducing tenants to the power they already have. The Red Hook Justice Center has its own housing court, and a long-time judge, Alex Calabrese, who’s been known to make surprise apartment visits to ensure repairs have been done.

Or how about this stat: 34% of cases at the Red Hook court are initiated by tenants. That’s tenants using the court to enforce accountability on landlords. By comparison, at Brooklyn’s central county courthouse, only 7% of cases are started by tenants. You’ll hear Ross in this clip refer to these as HP cases.

JOY: At the end of the day, there’s active protests going on in front of the New York City’s housing courts every day, post-pandemic. And there’s a running critique that’s been there for years that Housing Court is not a place to find fairness, especially if you’re a tenant.

And I think we look at our own data like that. We looked at our own court docket and realized that over 90% of our court cases were only controlled by the landlord filing, and the court system can’t just let one party run the court. That is an improper use of the state’s resources. And really, the court should be a place of fairness, that each party has an opportunity to have their issues heard. And that there’s remedies.

That’s one of the reasons why we are so passionate about making sure tenants know how to file an HP case, because it’s one of the very few procedural ways that tenant voices can enter into the court’s docket.

Before the pandemic, the New York City Housing Authority was bringing over a 1000 non-payment cases every year, and for a single development that’s only around 3000 units, they’re trying to evict one-third of the development a year. Issues that we kept hearing was residents said, “I’m withholding rent for repairs, I’m withholding rent for repairs.” So, we encouraged residents: “document your issues proactively. If you want repairs is your number one issue, file the court case to do it.”

It’s part of one of the reasons that it’s so unfortunate that New York public housing is essential to New York City, has been essential to New York since World War II, but are oftentimes still treated like second-class citizens. So, having the court get involved, this is a way for us to short circuit that and get access to city inspections, to get access to other resources.

WATKINS: Having housing court be a place where remedies are equally available to landlords AND tenants is not the norm across the country. The vast majority of cases are brought by landlords: either to collect rent or to evict someone.

Housing law is especially complex, and despite the stakes of losing your home, most tenants don’t even have the right to a lawyer. Here’s Shamus Roller again with the National Housing Law Project.

ROLLER Q&A: The eviction proceedings is the fastest civil procedure in almost every jurisdiction around the country. People sometimes get evicted in mere minutes. The default is that you get evicted. There are occasionally some defenses that you have, but it’s designed to produce a fast result for the landlord in which they can remove somebody from the housing that they own.

Watkins: Would you like to see a housing court that essentially defaulted to keeping people in their homes, wherever possible? Should that be the function of housing court? Or is it more at least be a neutral arbiter between landlords and tenants and try to ensure it’s a fair conversation?

Roller: I mean, what you’ve put forward is pretty dreamy, I think, in a lot of ways.

Watkins: I’ve been accused of that before!

Roller: I would go for some basic due process for all tenants in housing court. Housing court in most places does not resemble anything that most people imagine court being.

Watkins: It’s not Law & Order, is what you’re telling me.

Roller: It’s not!

Watkins: There’s no civil unit of Law & Order yet…

Roller: It doesn’t really look like that! In most cases, the tenants have limited abilities to cross-examine the people that are accusing them. They have limited ability to present any evidence. These sort of basic things around due process that you imagine are just not present in eviction court.

WATKINS: Eviction court. That is the name you often hear across the country. Red Hook’s approach is different: early intervention based on being embedded in a community, and a housing, not eviction, court, focused on giving tenants a voice. It seems like a model that could be replicated across the country.

SOUND: Door knocking, “Es Ross en la puerta!”

WATKINS: But let’s get back to our leak investigation. After talking to Ms. McKnight, and making our way through the construction maze, we’ve arrived at last at the apartment in question. Ross and Shamar want to get photos of the damage and then check with the neighbors if they’re having any issues.

A young man opens the door to us.

SOUND: Door opening, interaction in Spanish with tenant.

WATKINS: The damage in the kitchen walls is visible from the front door.

JOY: For the three past years we’ve been dealing with this leak, so we’re inside the kitchen, the wall has clear and very significant signs of water damage and it’s also in the bathroom. We’ll take some photos to add, for the court file, just to make sure that both parties, both tenant and landlord, understand the conditions.

WATKINS: Inside the kitchen, the wall is bubbling out from all the water collected behind it.

JOY: And that humidity smell is also not normal, that’s definitely related to the water. And then this is also the circuit breaker. There’s a water leak that’s directly leaking onto the circuit breaker and that by itself is a fire hazard and we have seen electrical fires due to leaks… ¿Y el baño?

WATKINS: It’s a similar story in the bathroom: bubbling, pock-marked walls and flaking paint.

JOY: And this light fixture is just so unsafe. It’s heavy smell of mold and moisture—that’s part of the reason that developed asthma, right next to where they’re trying… You can see the gnats—you see those all the time when water damage is in the plaster for too long…

WATKINS: Ross gets the photos they need and thanks the tenant as we make our way to the door.

JOY: En cuanto a la sala, qui lindo! The living room is so nice, they do try to keep it nice.

WATKINS: It’s true. There’s nothing the family living in this apartment can do on their own about the leak behind their walls, but the small living room just off the front door is immaculate.

We head to the next apartment but stop at the top of the stairs: the hallway floor is covered in grime and large flakes of paint hang from a corner of the ceiling.

JOY: But these common areas… Peeling paint by itself is a lead paint hazard. If there’s children that lives in this building, they’re always interacting with this lead paint hazard right here. It’s just not acceptable.

WATKINS: Ross will file a common space ticket: fix the peeling paint and mop the floor. He and Shamar head to the next door.

SOUND: Door knocking: “Hi it’s Ross from the Justice Center!”

CLOSING THEME MUSIC

WATKINS: That was our profile of the work of the housing team at Brooklyn’s Red Hook Community Justice Center. For more information about the Justice Center or the Center for Court Innovation‘s housing work, go to courtinnovation.org/newthinking.

Special thanks to Ross Joy, Marissa Williams, and Shamar McCall for their welcome and for their time, and to the whole housing team at Red Hook: Viviana Gordon, Luz Gonzalez, Daren Sealey, Albert Barnes, Jesus Hernandez, Court Attorney Edna McGoldrick, Chief Clerk Anthony Calise, and presiding judge Alex Calabrese. Thanks also to Fred Karnas, Rafael Moure-Punnett, Ignacio Jaureguilorda, and the estimable Bill Harkins.

Today’s episode was produced by myself and Julian Adler, and it was edited and mixed by me. Samiha Meah is our director of design. Emma Dayton is our VP of outreach. Our theme music is by Michael Aharon at quivernyc.com, and our show’s founder is Rob Wolf. This has been New Thinking from the Center for Court Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins. Thanks for listening.