We are an outlier in a country that is an outlier. What are we going to compromise about?

Of all the victories of progressive district attorneys dedicated to “ending mass incarceration,” Larry Krasner’s in Philadelphia in late 2017 seems like the most improbable. A career defense attorney, Krasner was notable for having sued the Philadelphia police upwards of 75 times. Krasner himself has likened his becoming D.A. to “the pirates taking control of the ship.”

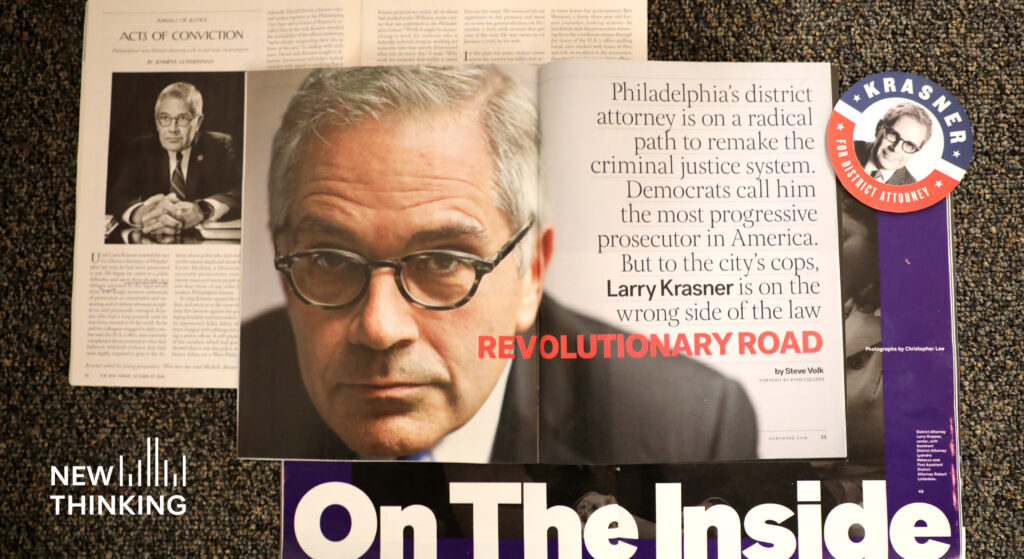

Larry Krasner addressing a rally in Philadelphia

He also seems, fairly or not, like the new D.A. most wedded to a “move fast and break things” philosophy. That pace of change has caused some tension inside Philadelphia’s criminal justice system—a city that not long ago was the most incarcerated of any big city in America. It’s also triggered an immense amount of national interest; in successive days at the end of October, three national magazines published feature-length profiles of Krasner.

In this discussion with New Thinking host Matt Watkins—part of our series examining the national debate over the power of prosecutors—Krasner describes the reforms he is putting in place, the challenge of ensuring they’re actually implemented, and why he has little patience for compromise in a city whose justice system is “an outlier in a country that is an outlier.”

Resources and References

- The Philadelphia Inquirer on judges pushing back against Krasner’s “rogue” Conviction Integrity Unit (01.19)

- Slate on “over-charging” and Krasner’s rethinking of his office’s approach to violence (12.18)

- Krasner on ‘Full Frontal with Samantha Bee‘ (10.18)

- Jennifer Gonnerman profiles Krasner’s “campaign to end mass incarceration” in The New Yorker (10.18)

- The New York Times Magazine on the power, and limits, of Krasner’s office (10.18)

- Newsweek on Krasner’s “radical path” (10.18)

- Street-level New York Times Magazine feature on the devastation wrought by Philadelphia’s opioid crisis (10.18)

- Krasner on Chris Hayes’s podcast, ‘Why Is This Happening?‘ (07.18)

- Shaun King in The Intercept: Krasner is exceeding reformers’ expectations (03.18)

- Slate on Krasner’s “wild, unprecedented” policy-change memo (03.18)

- The Philadelphia Inquirer on Krasner’s “dramatic” first-week ouster of 31 staffers (01.18)

The following is a transcript of the podcast:

Matt WATKINS: Welcome to New Thinking from The Center for Court Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins. Today is episode six in our series on the power of prosecutors.

Of all the victories of progressive DA’s dedicated to ending mass incarceration, Larry Krasner’s in Philadelphia last year seems like the most improbable. A career defense attorney, Krasner was notable for having sued the Philadelphia police upwards of 75 times. Krasner himself has likened his becoming DA to “the pirates taking control of the ship.” He also seems, fairly or not, like the new DA most wedded to a kind of “move fast and break things” philosophy.

Not surprisingly, that pace of change is causing some tensions inside Philadelphia’s criminal justice system—a city that not long ago was the most incarcerated of any big city in America. It’s also triggered an immense amount of interest across the country. So it’s a great pleasure then, to have District Attorney Larry Krasner on the line today from Philadelphia.

DA Krasner, thanks so much for joining us.

Larry KRASNER: Delighted to be here. Thank you, Matt.

WATKINS: Prior to this you were a lifelong defense attorney and something of an antagonist of the system. You had a front-row seat to what you’ve called in a couple places, “the slow- motion car crash of the criminal justice system.” What role do you think prosecutors played in this car crash, one I suppose we now call mass incarceration?

KRASNER: I would say that they built the car, maintained it poorly, tuned it incorrectly, and deliberately drove it into the wall at the highest speed possible while intoxicated. I would say they played a pretty big role in causing a slow-motion car crash and they did it in their capacity as prosecutors working in the office. But also very often, they then went on into politics where they had sway over legislation or where they had discretion as elected officials to do things in positions other than chief prosecutor, and frankly, continued to do bad things.

WATKINS: Do you find that your position on prosecutors has changed at all, now that you actually are one and are in fact in charge of several hundred of them?

KRASNER: You know, I think that all of us should learn, and I think that I have learned. I’ve been chastened a little bit about some of the assumptions I’ve made. I think I didn’t fully understand to what extent some of the bad culture was the result of external pressure. I, for example, really was not happy with how prosecutors seem to be using victims and pandering to victims in certain ways, for their own political purposes. That part I saw.

The part I didn’t see is the consequence of being really honest with victims, of talking to the family of a homicide victim and telling them, “Listen, there are five different levels of homicide, and I know how much you loved your child, that is a grievous loss to all of us. But, under the law this is third degree, this is not first degree.” I didn’t realize the extent to which simply being honest with them, and not using them for political reasons, would have consequences, and the consequences are pretty severe.

The media is fond of having conflict stories, so to the extent you actually stand up for what is the right thing, and you’re honest with victims, what you’re getting back is often a drubbing in the press. So, I guess in this position I’ve come to understand there are certain pressures that go with the amount of power, there’s certain pressures that go with the high level of attention on the office, that may have shaped that culture. I have to be honest about the fact that I have a little bit more compassion for some of the bad decisions that were made for the wrong reasons, but they were made under more duress than I realized.

WATKINS: It seems like this question of victims is a difficult balance to strike, I would think, for progressive prosecutors who are trying to distance themselves from this traditional concept of, that the prosecutor is there, a big part of the job is to represent the victim. And you have had, I think you’ve acknowledged, some growing pains in dealing with that. How do you work to make the office more progressive then, and and not lose the trust of victims and their families along the way?

KRASNER: You know, to me this is a problem that’s frankly analogous to what it was like when I was a private criminal defense attorney. There were a lot of competitors out there, who were private criminal defense attorneys who would lie to the family of the defendant. They would say, “I guarantee you will win,” which is strictly unethical; they had no basis for doing that. And as a consequence, their careers were easier, they were more successful, they could land a client by doing things that were unethical. I was winning more cases than they were, but I was telling the truth. And the consequence was, I lost money, I lost business over it.

Well to me, this is analogous. I’m actually telling the truth to people, I’m being honest with them, and that is not what political prosecutors have done in the past. They have pandered, they have used, they have told victims that they represented victims, when the law is very clear that they do not, strictly speaking, represent victims. They represent every single person in the Commonwealth, and one of those people would be the victim or the survivors, and another person is the defendant. And the rest of people—and there’s only 1.6 million of them in Philadelphia—are the people who are otherwise affected by the whole situation.

So the reality is, when you are ethical and you take your oath seriously, and you’re honest about it, it’s more difficult to play by the rules than it is to cheat. And I’m going to bear the consequences of that, because that’s just the reality. But eventually the consequence of playing by the rules and being honest about it, is that over a period of time you gain people’s respect, you gain their trust, they see that you’re actually trying to do the right thing.

I mean, this is the first administration that got a million-and-a-half dollar grant to produce a network of 12 advocates who go to the homes of family members of homicide victims as soon as the killing occurs, and I mean as soon as it occurs, and go into the house to tell the family what’s happened. And then these advocates stick with the family for 45 consecutive days, helping them through every painful step of this traumatic process. No prosecutor in Philly has ever done this before. And there is no way to look at that and say that this office doesn’t care about victims.

But that is what we are doing on the one side, while on the other side the criticism is, “My child was killed, I’m upset. This has to be first-degree murder.” It’s not a first-degree murder if it’s not a first-degree murder. That’s why we have five levels, and like it or not, we’re going to take the steady course, the slow course, which is tell the truth to people at the beginning, even if they don’t always like it. Eventually I think, much as in my career as an attorney, eventually you gain their respect and their trust. And they realize that this is better for them, than being lied to from the jump.

WATKINS: And then along the way you’re just going to have to accept that kind of blowback that comes from those segments of the press that were never very sympathetic to your enterprise from the beginning, I guess.

KRASNER: Not only are we going to have to accept it, we already do accept it. First of all, there are a lot of great journalists in Philly and elsewhere, and I have a tremendous respect for them. My father was a writer, he also did a certain amount of journalism. He was a career author. I mean, that’s what he did, right. So I have tremendous respect. I’ve defended free speech as a criminal defense attorney my whole career. There’s probably not any attorney in Philadelphia, who did more to defend free speech in the criminal context, than I did. There’s a couple others who did just as much.

So, this is an issue that’s near and dear to me. But part of the problem is, that there’s an old easy story, that certain lazy journalists can tell, and it’s an antagonistic story where the person who did the crime is 100 percent awful and needs to be drawn-and-quartered, and the victim of a crime is a perfect angel with white snowy wings, and the only proper healing for that person’s wounds, is drawing-and-quartering.

It’s a very old trope that came from William Randolph Hearst it sold a lot of papers, it’s still a lot of click-bait. And there’s a much more intelligent, much more nuanced, much more interesting kind of journalism around these issues, that does talk about policy and that sees the bigger picture.

Some journalists just don’t want to go there. It’s hard, it’s a lot of work, it requires you to know things and learn things. And we’re always going to have a problem with journalists who don’t want to go there. But the ones who do, I think, are going to find out that what’s happening in Philly is a really interesting read.

WATKINS: So you’ve put in place a lot of changes since you took over the office, or at least you’re making a lot of attempts to change that policy from the top. There’s significant bail reform when it comes to non-violent crimes; you’re bringing balancing back to sentencing as you put it; changing how your office handles low-level charges; how it deals with police misconduct; having prosecutors announce in court the cost to the taxpayer of each sentence, often very long ones traditionally, involving incarceration.

Are you comfortable with this public image, that I’m sort of arguing you’ve cultivated, of the “move fast and break things” guy? Does that help you accomplish your goals?

KRASNER: I’m comfortable with move fast, I mean, I don’t know that I’m really breaking good things. I think I’m breaking bad things. And I’m breaking bad things that never were meant to be. I mean, the United States was never meant to be the most incarcerated country in the world. It flies in the face of our ideals and the good part of our history. It just doesn’t make any sense.

So, to the extent we’re breaking that, well, there’s other countries that had to break a few things to get back to freedom too. That part I accept. But for the most part, I really don’t think we’re the radicals. I think the radicals were the ones who took hold of the system 40 or 50 years ago and turned this country into a gulag, and did all of these things that have been incredibly destructive of everything that makes us safe, by which I mean public schools, treatment, that sort of thing.

WATKINS: But as we’re trying to end mass incarceration I think the consensus is it’s not something that can be done overnight; it’s something that is going to be taken apart in pieces, the same way that it was constructed. So I’m just wondering, how do you work to ensure that the changes that you’re trying to implement are going to last—not just through your tenure obviously, but outlast your tenure and be something that your successor can carry forward?

I’m sure you’ve heard the grumblings that you’re moving too fast or not bringing partners with you enough, and referring to yourself as the pirate taking over the ship, for example might not be designed to win over the skeptical people out there. So do you feel you’re learning something about compromise? Or is just not a time for compromise?

KRASNER: I mean, compromise is not my specialty honestly. Let’s be honest! But compromise with what? We can sit down with a dictator and say “let’s all be reasonable now,” but a dictator ain’t gonna be reasonable. You are dealing with a country that is the most incarcerated country in the world. We’re looking at a system in which there is an even greater division of wealth all the time.

In Pennsylvania, for example, we have the highest level of excessive supervision of parolees and probationers of any state in the United States. Everybody else got a 500 percent increase in their mass incarceration over the last 30, 40 years, we got an 800 percent increase. We have the second-largest number of people doing life without parole, and I think the fifth-largest death row. You know, we are an outlier in a country that is an outlier. What are we going to compromise about?

I mean seriously, this is a country that went for Donald Trump, and I know for a fact that the legislators in Pennsylvania who are writing all these laws for mandatory minimums, and coming up with these ridiculous high sentencing guidelines, and coming up with all of this regressive type of legislation, I know for a fact that their counties benefit from incarcerating Philadelphians for long periods of time.

The problem that they have, and it’s a problem, is that in the leading criminal justice jurisdiction in Pennsylvania, the district attorney has a lot of discretion. He does not need buy-in to make a decision in several different areas, not every single one, but in several different areas. I see absolutely no reason why I should be seeking buy-in from people who very cynically and unnecessarily wielded power in negative ways, when the voters made their decision in a landslide that the decisions within my lane should be made by me.

I mean, sure, we want buy-in, but it comes in different forms. I think that the kind of compromise we’re looking for is one where we move swiftly in the areas where we have control, and then we have the ability to talk to the opposition about meeting somewhere in the middle with their power and our power already being defined.

WATKINS: I take your point about what exactly would you be compromising with. But when you talk about the other side, the other side doesn’t simply disappear because of one progressive former defense attorney’s election. And you’ve spoken in a number of interviews about, you know you can have the best-made policies, but culture eats policy, and culture is extremely strong and entrenched in the criminal justice system. And as you’ve just laid out, we’re talking about decades of going in a particular direction. I just wonder how you think about trying to get these changes into place, when you have this entrenched culture often on the other side?

KRASNER: When you talk about within Philadelphia, for example: you have a lot of judges who are actually just fine with what we’re doing. I would say about 98 percent of what we do, in terms of things like guilty pleas, or recommendations for new sentences for what used to be juvenile lifers, have been accepted. It’s extremely rare when we are getting resistance from judges in that regard. And that’s because either they agree with us, or they feel like our discretion is being used appropriately.

So, all that is coming. But within the institution, within the DA’s office itself, for example, what are we doing? Well, simply put, we’re hiring. We have been to about 25 different law schools around the country. I went myself. I went with my first assistants, and I did that, unlike pretty much any other DA’s office in the country, to so many schools, because we don’t want this office to be an office that just draws from local schools, that is considered sort of a B-level District Attorney’s office. We want it to be the destination district attorney’s office for young, progressive talent, who really want to see a change in the criminal justice system.

So far, we’ve been extremely successful. We have something like an 85 percent rate of acceptance from these incredibly talented, hard-working kids who have a moral compass who want to come here. And I think that’s the key to it. Because you’re right, this isn’t getting fixed overnight. But what we need to have is another generation of people who are going to finish the mission. And that generation of people is being hired straight out of law school, but it’s also being hired as mid-career people, so that we have this critical mass of people who believe in the mission, and who are going to carry it on.

WATKINS: I can understand why that new generation is so important to instilling a new culture. And of course you also had to engage in some fairly high-profile firings at the beginning of your tenure of people who you felt simply weren’t going to be receptive of the message. But, I’m wondering more generally, what kind of reports you’re getting about to what extent your policy shifts are being followed by the assistant district attorneys, the kind of shock troops in the courtrooms? Are they following this message, and also what kind of reception are they’re getting from the system?

KRASNER: It’s always really difficult to have perfect intelligence. We have an office of 600 people, we are funded for about 300 attorneys. You obviously have an awful lot of attorneys in an awful lot of courtrooms at any given time. And the reporting back is not perfect. I would say, we do not have 100 percent compliance, we don’t really expect it. Culture change isn’t that quick.

But we are having good compliance, and we can tell that we’re having good compliance, because we’re looking at certain metrics. As we look at the comparison between the sentences that are being generated in courtrooms now, and the sentences that were generated in courtrooms a year ago, we can see that there is a very serious downtick, that the numbers are much lower. That’s data across the board that is consistent with our policies, and strongly suggest that those prosecutors are asking for what we want, and the judges are giving what we want.

If you look at the serious downtick in the population of the county jail, which has gone from 6,500 to a little bit below 5,000 now, those results are very strong. And when you harvest the metrics, you see that they coincide exactly with a period of time when our bail policy and also our policy on sentencing of non-violent, non-sex offenses went into play. So, we can see in these broader statistical ways these things. Are there anecdotal situations in which judges are saying, “I’m not going to do that,” and prosecutors are probably winking at them? Yes, I’m sure that there are.

But I have tremendous respect for judges. I don’t expect them all to agree with our policies. But we are seeing from harvesting the metrics that we’re having the effect we wanted to have. We don’t need every single ADA—assistant DA—to do right. We don’t need every judge to agree with us—God knows we do believe in the independence of the judiciary. But I think that we are getting there.

And we’re looking forward—as we have this transformation of personnel, as we have additional education, as people see the policies work—we’re looking forward to having even more buy-in and being able to be more effective in enacting our policies.

WATKINS: Have you come up with strategies for supporting the young ADAs? Let’s take someone fresh out of law school who’s very in line with what you’re trying to do, but they’re encountering, say, significant pushback from judges, or in their cooperation with police. Have you figured out what you can do to try to support them in their role?

KRASNER: The first thing that we did is we came up with a completely new training program here. The training was rather light in the past, and we put a lot of money and a lot of time into a collaboration, which we had with Adam Foss.

And it went from shortly after Labor Day until these new attorneys passed the bar, which would have been, for the most part, the end of October. So like eight, nine weeks—much longer, and the training had very much to do with the new mission, and how to act around the mission. So that’s just one example.

As we move forward, and more of the people who are coming are our hires. You should know, that the new class that just came in, half of them were hired by the old administration, and half of them were hired by us, just because of how the hiring cycle happens to work, but as we move forward, our intention is to take the new crop of attorneys, and to visit with them with some frequency, see where there are issues, and be supportive in various ways.

WATKINS: You made a reference earlier to metrics and getting a handle on what’s actually going on, on the ground. The traditional metric for a prosecutor has been wins—securing convictions, that’s a win. You obviously need to get a new concept of what it means to be successful and new metrics in place to define that success.

KRASNER: As we continue to harvest more data, I think that we are going to develop a bigger system. I mean the immediate short-term thing is to change the handwritten evaluations that are done periodically of prosecutors so the supervisors have different criteria. And those criteria in my mind, should include things like: has this prosecutor ever come to you with a well-placed explanation for what they think is wrong with the case? Have they ever come to you and said, I think this was a violation of the Fourth Amendment rights. Have they ever come to you and said I think this person may be innocent. Or have they ever come to you and said I think that this punishment may be excessive.

Because if they don’t come to you some of the time, saying things that are in agreement with the defense, and some of the times going on the other side, then there’s not really a sense that the door swings both ways. And that there’s any kind of evenhandedness at play.

That will get you so far, you know, and as people start to understand that our job is not just to win cases, including cases against innocent people, but our job is to win cases when it’s appropriate, our job is to divert cases when it’s appropriate, it’s to never bring cases when it’s appropriate. And frankly, it’s to reject cases when they can’t be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. When there starts to be a culture around that, certainly those handwritten evaluations, which are very subjective, will become useful.

What I would really rather see though, and I think it’s a possibility that we should look at, is I would rather see some kind of harvesting of metrics that would also tell us the following: We always talk about “a certain prosecutor didn’t get enough time against a defendant.” We know that because defendant Willie Horton went out and did something terrible 20 years later.

It’s a purely negative report card. You don’t lose any points for keeping someone in jail forever who didn’t need to be there, you only get points for keeping people in jail forever, so they never do a bad thing. Well, if you locked up every single person on the planet, they’re not going to be out on the street committing homicides. But that doesn’t really mean you make the world a better place, it means you made the world a jail.

I would like to see kind of a metrics that’s almost like what you have with an insurance company: when you took a risk on somebody, were you good at it? In other words, when you took somebody who had a felony drug case, and you said we’re going to divert this case, because we don’t want you to lose your ability to participate in the economy with a felony conviction, did that person then stay out of trouble, get a job, become a provider and a homeowner, and a taxpayer? That should be a plus on your report card.

WATKINS: On the topic, then, of not making the whole world a jail: You’ve made a lot reforms to how your office is handling non-violent crimes. Perhaps there’s been understandably fewer changes tied to charges involving violence, and of course we can’t undo mass incarceration in this country simply by focusing on the non-violent drug offender. Obviously, offenses involving violence are kind of the hard nut of reform, and I wonder what your plans are, to belabor a metaphor here, to move the needle on that issue?

KRASNER: So, it’s a great question, and honestly I don’t think it’s a hard nut.

WATKINS: I guess I mean the public selling of it is a hard nut.

KRASNER: No, I hear that, and let me tell you what I’m getting at. Violence is a fairly ambiguous term, and the truth is when we think of violent crime, and what’s flashing through our minds is, a serial killer, or it is a stranger rapist, or it’s a vicious fight in which someone is almost beheaded.

But when you’re talking about things like two kids having a fight in school yard, it wasn’t that long ago in Philadelphia that the kid who gave the other one the black eye, would end up in juvenile court facing aggravated assault! And probably aggravated assault as a first-degree felony, because they were so in love with over-charging.

So, we’re going to have to differentiate between things that could be called violent, but are not that concerning, and things that are truly concerning and are truly violent, and tear apart the fabric of society. And when we start doing that, it actually significantly shrinks the number of offenses that fall into that category. That’s part of it.

And then the other part of it, if I may quote my 84-year-old first assistant, Carolyn Engel Temin, who has been a prosecutor, a defense attorney, a judge for almost 30 years, and then did international human rights work, and therefore has the institutional memory and a 60-year criminal justice career to remember how we used to sentence before the era of mass incarceration… She has this phrase, and the phrase is: “Five is the new one.” Meaning, things that are just like what’s done today—people hurting people, which went on then and it goes on now—used to be sentenced at 1x, and now they’re sentenced at 5x.

There just came a moment when the culture and the politics around this, felt like five years was one year, and 25 years was the former five years. Exactly why it happened, I mean I think there’s a lot of politics in it, I think there’s a lot of sort of extravagant culture in it. But five is the new one. And we need to think seriously about whether some of these offenses, where people get 50 years, maybe should be 10. Or some of the ones where they get 10, maybe should be two. The notion that there is incarceration that is owed as an aspect of accountability, as an aspect of deterrence, et cetera, doesn’t mean it has to be as big and amplified as it is.

So, we’re going to have to look back and see things, like, how did we used to punish lower-levels of homicide, as opposed to how we do it now, and why do we do it now? Why is it that young attorneys, with whom I speak all the time, when they’re recommending a sentence on a serious case, they always seem to speak in terms of, “we’ll give them five years, we’ll give them 10 years, we’ll give them 15 years, we’ll give them 20 years.”

I don’t know what the fixation on five is, or multiples of five. But if 10 is really such a great idea, what’s wrong with six? And that’s often the question I’ll ask. They’ll say to me, “well, I think that this one is worth 25 years. And I’ll say, well what’s wrong with 21? What’s wrong with 13? Please explain to me why that particular number applies.”

Because we’re not talking about M&Ms, and we’re not talking about Skittles, we’re talking about, not only years of human life, but probably more importantly honestly, we’re talking about this incredible quantity of national resources that are not going for teachers and firefighters and police officers and social workers, and economic development. We are talking about years as if they’re free and they’re not free.

WATKINS: …which seems like such a question of culture, I mean, what a case is worth?

KRASNER: Right, it does. And again, these decisions are usually made by judges and they’re made by prosecutors who have not spent time in jail. I’ve never served time in jail, but I have spent more than a year of my life going to jails during daytime hours, and visiting people in many, many different jails. And it does give you a little bit more insight into how long a year in jail really is. It’s a long time, it’s a freaking long time. It’s a freaking long time for taxpayers to pay for, but it’s also a long time to be in a cell.

I’m not sitting here saying serious offenses deserve one year, they don’t, they deserve longer, often a lot longer than that. But there are whole swathes of offenses for which we used to not incarcerate in the 1970s, and now we incarcerate for them. And there are minor assaultive offenses. There are two guys having a dispute in a bar, and one of them punches the other one and knocks out a tooth. And they’re both union guys and they hug it out.

In those cases, if you don’t derail the system, under the sentencing guidelines, it could put the one who knocked out the other one’s tooth—which is usually how it works, you usually blame the one who injured the other one… They could put that one in jail potentially for a year or two. You know, losing the job, losing the ability to support the family, losing the family home, losing the health benefits, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Nobody, no sensible human being thinks that that’s a great outcome for two guys who had too much to drink at a bar and one punched the other and popped out his tooth. But that is where our system will take us, if we’re not willing to look at violent offenses and say: that is one requiring severe punishment, and these are not—these are ones that we have to view in a different way.

WATKINS: Then I wanted to end with a question about this larger movement that’s taken shape and grown at a really remarkable pace, to organize the public around a public education campaign about the power of prosecutors and to organize voters to get more progressive DAs into those positions.

It seems to me that there is something of a fault-line within that movement potentially which is that, on the one side you have people who will say that prosecutors currently have too much discretion, they have too much power; that that discretion needs to be reined in and some kind of guidelines be put in place. And then on the other hand, you have people who are saying, no, the system actually needs prosecutors to have this kind of discretion. We just need to ensure that they know how to use it, and that we’re putting people in place who are going to use it well. I wonder if you see that as a bit of a fault-line, and if you accept it, where you would position yourself?

KRASNER: It’s a tough discussion, because what we’re really talking about is a history of discretion being considered sacrosanct and good, so long as the people exercising it were unmerciful, retributive, and draconian. All of a sudden, when we see that voters in major areas—and those major areas are very important for criminal justice because they are the drivers of mass incarceration, among other things; they’re also the locations where there’s the biggest issue with public safety—when we finally have some people in these positions who are progressive, immediately there is a push to take away their power and their discretion.

I think it all boils down to a different issue, which is: do you believe that human behavior and individual justice can be reduced to a matrix? Can it be reduced to a set of guidelines? Can it be reduced to mandatories? In other words, can it all be reduced to stereotypes? And the answer to that is no.

We have a history of case law, especially American and English jurisprudence, where you don’t try to predict every possible thing that might happen in the future, you try to make a decision about an actual fact pattern of something that has occurred. And then you sometimes look back at the decisions you made for guidance in the future. And there’s a big difference.

When a state like Pennsylvania says, “If you’re convicted of first-degree murder, you either get life without any possibility of parole, or you get the death penalty,” then that is a generation of legislators, many of them not lawyers, never been in criminal justice, probably just motivated politically, who are saying, “I don’t care what specific circumstances there are in 50 years, I got it all figured out. This monster must be in jail forever because of a particular act that occurred.” And that is nonsense. That’s not how the world works.

To a very large extent, we’re just going to have to admit that sentencing guidelines have been a tremendous failure, that mandatory sentencings are negative. These are nothing but the codification of stereotypes. And if we have a situation in which there is no discretion, or we limit discretion, what we are doing is we’re saying: the specifics of the person don’t matter, the specifics of the incident don’t matter, our judges can’t be trusted to judge. We have to essentially not just handcuff all of the defendants, we have to handcuff all the participants in the system; we have to tell them these are the stereotypes you must follow.

So, I’m very much on the side of discretion. It’s like anything else, it’s power that can be abused, and all power can be abused, but I’m very much on the side of discretion. And I say that partly because I see a generation of people who are coming up, who I think are right-minded, they’re much more progressive, they don’t find it fearful to say, “well obviously there’s a history of racism.” They don’t find it fearful to say there’s problems with the death penalty, they’re not afraid of talking about how excessive policing has negative consequences.

And I think we need to leave discretion in the hands of the next generations coming up, because they’re going to do a lot with that discretion to make things better, until the old people who write the laws catch up.

WATKINS: I take your point on that, but when you describe yourself maybe a bit jestingly, now as a prosecutor, as a public defender with power, that suggests to me—and you seem very well positioned to answer this question having done both roles—that you don’t see the contest between the prosecutor and a defender (and generally it’s a public defender, because most defendants are indigent), that you don’t see that contest as currently fair, as a fair fight. Are there other things we can do to ensure that it is a fair fight in the defendant and the victim’s interest?

KRASNER: So just so we’re clear, the full quote, which isn’t always reported, is that progressive prosecutors—and this was done in the context of recruiting, talking to young law students about these ideas—they are neither public defenders nor are they traditional prosecutors. They should view themselves as being prosecutors with compassion, or public defenders with power—a third category.

What I’m getting at is I actually think that the prosecutor’s job is almost judicial, in a way. We have to look at all the circumstances, and we have to be willing to say, “well, I probably could get that conviction, but it would be wrong, because I don’t think that person did it. I probably could win a motion to suppress, but it would be wrong because I’m convinced that the police officer’s information here is a lie.” We have to be willing to be a justice filter on the system, which to me is analogous to a judicial function. It’s just that in many ways, it’s a more powerful judicial function, because there’s one DA’s office in Philadelphia, but there are well over 100 judges staffing a lot of courtrooms.

And if the decisions are made from the top and that culture is established, then there’s a filter at the front of the system, which is what cases is the prosecution willing to take to court for trial. And there’s a filter at the other end of the system, which is either a jury, or it is a judge, and hopefully a good judge, hopefully a judge who’s even better than the prosecutor, to make sure that the results coming out of the system have integrity.

Essentially I think what that means is there has to be an adversarial relationship with the defense, but it cannot be adversarial to the truth, and the prosecution must recognize that there are certain things the defense can do, in the context of carrying out justice, that we can’t do.

One thing they can do is talk to their client, and they can get evidence, and they can bring it to us, so that we can, in the proper case, recognize the innocence of a defendant, or the proof that something improper and in violation of people’s rights was done. That only works if they trust you, because they don’t have to bring anything, And I can tell you, when I was a defense attorney, dealing with a draconian prosecutor’s office, most of the time I had to make a strategic decision not to give them the information because all they would do with it is take the extra time and try to destroy that evidence, or you would find magically that their witnesses modified their testimony. Those were the consequences that I used to have as a defense attorney when I came to a cynical prosecutor’s office, with that kind of info.

We can’t be those cynical prosecutors, because if we are, we’re not going to get that kind of information, we’re not going to get the alibi that we can check out in a fair and even-handed way and find out it’s actually true. That’s, I guess, what I’m getting at is there’s a point where it’s so adversarial it becomes adversarial to the truth, because there’s no honest exchange of information.

WATKINS: Yeah, the progressive prosecutor movement has been around for long enough now that it’s acquired a couple of a tag lines, and one of them would be the job of the prosecutor is not just to secure convictions, it’s to seek justice. I find in what you just said there, often justice is left undefined, but you’ve put some real meat on the bones there, of what we mean when we talk about justice.

KRASNER: Well I mean, you know, some of that is what I feel, some of it is just sort of what obviously flows out of case law and requirements of what prosecutors are supposed to do, according to the US Supreme Court, or according to our association standards.

WATKINS: Well listen, DA Larry Krasner, I thank you very much for taking the time out of what I know is a really busy schedule to join us here today, and obviously we’re all going to be keeping a close eye on your ongoing work. So thanks so much.

KRASNER: Well don’t keep watching me, keep watching the work, because there’s a hell of a lot of people here and other places, who are doing great work, and this is really about a movement, not about any individual, but thanks very much.

WATKINS: Indeed, well that’s good advice. I’ve been speaking with Larry Krasner. Larry Krasner is the District Attorney for Philadelphia.

For more information on this episode, and all of the episodes in our prosecutor series, and that includes transcripts and some suggestions for further reading, you can visit our website that’s at courtinnovation.org/newthinking.

Technical support today from the indomitable Bill Harkins. Samiha Meah is our director of design; she’s the person who makes those episode pages on our website look so good. Special thanks as well for today’s episode to Somil Trivedi, Sherene Crawford, Liberty Aldrich, John Butler, Emma Dayton, Hannah Raskin-Gros, Mike Rempel, and Jonathan Monsalve. Our theme music is by Michael Aharon at quivernyc.com. And our show’s founder is Rob Wolf.

This has been New Thinking from the Center for Court Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins. Thanks for listening.