-

Krystal Rodriguez

-

Michael Rempel

In January 2020, New York State put into effect sweeping criminal justice legislation, strictly curtailing the use of cash bail and pretrial detention, overhauling rules governing the sharing of evidence, and strengthening measures intended to ensure a defendant’s right to a speedy trial. These analyses (summary and comprehensive) explore the potential implications of the reforms to the use of bail.

Key Findings

- In New York City, 43 percent of the almost 5,000 people detained pretrial on April 1, 2019 would have been released under the new legislation. Outside of New York City, the effects could be even greater.

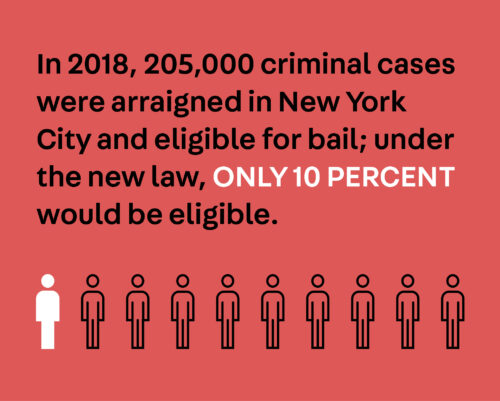

- Of the almost 205,000 criminal cases arraigned in New York City in 2018, only 10 percent would have been eligible for money bail under the new law.