Where this leads is less a question of what the data says, or even a question about the technology. It really reduces down to values.

About two out of three people in local jails haven’t been found guilty of any crime. Instead, they’re being held awaiting trial, often because they can’t afford bail. What if a mathematical formula, based on enormous datasets of previous defendants, could do a more objective job of identifying who could be safely released?

That’s the promise of risk assessments, but critics call them “justice by algorithm,” and contend they’re reproducing the bias—especially racial bias—inherent to the justice system, only this time under the guise of science.

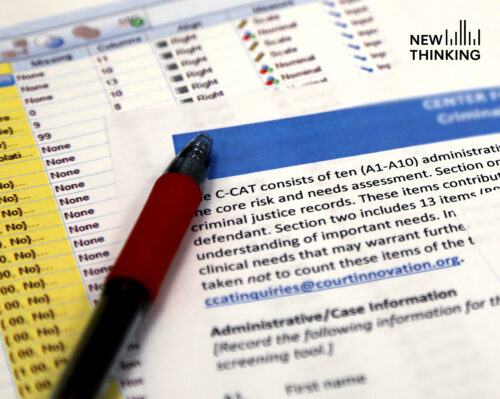

To help sort through this often heated debate, New Thinking host Matt Watkins sat down with two of his colleagues who work with jurisdictions across the country looking for ways to reduce their use of jail, and who have thought deeply about the ramifications of risk technology, even developing and analyzing their own assessments for use in the courtroom. Sarah Picard is a research director at the Center for Court Innovation, and Julian Adler is the director of policy and research.

Perhaps surprisingly, much of the focus of the conversation was on values. While acknowledging the reasons for wariness of risk-based decision-making, both Picard and Adler stress the assessments themselves are only tools, tools that produce no predetermined outcome. Instead, they say, the onus is on practitioners to decide how they want to use them, and to do so transparently, open to course-corrections, and with an eye on reducing incarceration overall, and promoting fairness.

Resources and References

- Roadblock to Reform—The American Constitution Society documents the formidable challenge of risk assessment tool implementation (11.18)

- Pew Research Center: Public Attitudes Toward Computer Algorithms (11.18)

- Risk, Values, and Pretrial Reform (09.18)

- Arnold Foundation to Roll Out Pretrial Risk Assessment Tool Nationwide (09.18)

- Videos of Dallas Bail Hearings Show Assembly-Line Justice in Action (09.18)

- Philadelphia Advocates Protest Technology That Assesses a Defendant’s Level of ‘Risk’ of Offending (08.18)

- The Use of Pretrial “Risk Assessment” Instruments: A Shared Statement of Civil Rights Concerns (07.18)

- Risk Assessment and Pretrial Diversion: Frequently Asked Questions (06.18)

- In Defense of Risk-Assessment Tools (10.17)

- Risk Assessment: The Devil’s in the Details (08.17)

- Machine Bias—There’s Software Used Across the Country to Predict Future Criminals. And It’s Biased Against Blacks (05.16)

- Eric Holder: Basing Sentences on Data Analysis Could Prove Unfair to Minorities (08.14)

The following is a transcript of the podcast:

MATT WATKINS: Welcome to New Thinking from the Center for Court Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins.

Today, as promised in our episode title, we’re taking a deep-dive into one of the really hot-button issues in criminal justice reform: risk assessment. Put simply, if you’re charged with a crime, who—or what—gets to decide whether you can be released while you wait for your trial?

Judges used to make that decision on their own, but now a new database-methodology is in use across the country. It claims to be free of bias—objective. But to critics, it’s “justice by algorithm,” with bias, and especially racial bias, built right into the data. Given that about two-thirds of people in local jails are being held awaiting trial, the stakes over how pretrial decisions get made could hardly be more urgent.

So, for those reasons and more, I’m very happy to be joined today by two of my colleagues who work a lot on these questions. Sarah Picard is a research director here at the Center for Court Innovation. Julian Adler is our director of policy and research.

Sarah, Julian, thanks so much for joining me today.

JULIAN ADLER: Thanks for having us.

SARAH PICARD: Hi. Thanks.

WATKINS: I thought we could start by taking a step back, take a big-picture look at this, and start with the issue of pretrial reform itself, which has become such a focus of energy in the criminal justice reform community. Could we say a bit about why this has become such a focus and particularly, this concentration moment over the decision about who gets released and what happens to people awaiting trial?

ADLER: There’s a growing recognition that local jails are a major driver of mass incarceration in the United States. Every year, we see between 11 and 12 million new admissions to local jails across nearly 3,000 local jail systems, each with their own idiosyncratic procedures for handling arrests as well as pretrial decision-making.

At the same time, there’s an equally profound recognition, both among reformers as well as the general public, that the majority of that local jail population is pretrial, meaning innocent until proven guilty under our constitutional system, and yet, the majority of folks held in jails, rather than being released pending trial, are there not because they’ve been convicted of any crime, but because they can’t afford to pay money bail. This has really been a flash-point, an awakening, and really has galvanized reformers to look much more searchingly at how we can reduce mass incarceration at its front door, at the jailhouse door.

WATKINS: To the extent that risk assessments could function as a replacement for a system of money bail that many people are saying is unfair, could we just start by explaining what risk is being measured, essentially, and what exactly a risk assessment is?

PICARD: Risk assessment tools typically measure one of two outcomes that are of interest at the pretrial stage. One is the probability that a defendant would fail to appear for their court date or that a defendant would be arrested for new criminal activity while awaiting trial.

WATKINS: Right. How does that risk get calculated?

PICARD: Risk typically gets calculated based on a range of factors that rely heavily on the person’s criminal history. Typically, prior convictions, prior failures to appear in court, some demographic factors including gender and age, current open cases, sometimes factors such as current charge and the seriousness of current charge.

WATKINS: These are what are known as actuarial risk assessments. It’s essentially an algorithm that is pulling in data points about a defendant and then balancing and weighting them to generate a score?

PICARD: Yes, that’s correct. Algorithmic risk assessments are able to do something that typically a professional might not be able to do with all of this information at their fingertips, which is they combine all the information, and based on what prior data tells us about how each of these factors would influence the outcome of interest—failure to appear or re-arrest—they weight and score each item, combine them, and then they are able to classify each defendant as high-, moderate-, or low-risk for new arrest.

WATKINS: Which then influences the decisions that get made about whether release or bail…

PICARD: Exactly.

WATKINS: Julian, could you make the case for risk assessments, why we might need them, and I suppose with reference to what the no-risk-assessment status quo has been?

ADLER: Proponents of risk assessment make a number of arguments. This isn’t necessarily an exhaustive list, but these are some of the most salient.

One, that judicial decision-making or discretion is opaque; that judges make decisions in a manner that is heavily influenced or potentially influenced by bias—assorted biases: cognitive biases, implicit biases. And that what risk assessment has the potential to do is to standardize pretrial decision-making in a manner that is knowable, that is more objective, and that presumably could control for bias.

There’s also an argument that when it comes to pretrial, the only suitable justification for pretrial detention would be some kind of imminent threat to the public safety or concerns that an individual, if released, will not appear, will not return to court. What risk assessment attempts to do is to focus the pretrial calculus on those particular outcomes and to control for all the other things that might complicate and influence a judge’s decision whether to release or to hold a defendant.

The other major point the proponents point to is by basing the pretrial decision on an actuarial prediction of risk—either risk of failure to appear or risk of further involvement in the criminal justice system—is it takes money out of the equation. An argument that proponents make is that money doesn’t do anything to protect the public safety, that a wealthy person, even if he or she or they poses an imminent risk of harm to others, has the option to buy their pretrial freedom, whereas an individual who does not cannot, regardless of risk to the public or potential risk to not appear in court.

WATKINS: The other thing that we know about the way release decisions actually happen on the ground is they happen very, very quickly. Bail hearings are often pretty cursory affairs. That would be another case you could make for risk assessment, that if judges are being forced to make such hasty decisions, the risk assessment is something that can give this quick, objective—although that’s a term we’ll get into—assessment and something that’s meant to be a supplement to a judge’s discretion, not replacing it.

ADLER: Yes, when individuals have to make complicated decisions very quickly, neuroscience and cognitive science shows that they tend to rely on heuristics. In other words, they rely on biases or mental shortcuts to make those decisions. Judges, like any other human actor, will do something similar. In a lot of criminal courts, a judge may have just a minute or two to arraign a complicated case, to weigh the potential weight of the evidence, to hear arguments from both the people and the defense, and to then make a decision about an appropriate pretrial outcome. That’s incredibly difficult to do.

WATKINS: Sarah, given that risk assessments have this potential at least to help produce more standardized, consistent, maybe even objective decisions, how much promise do they show for contributing to an overall goal of decarceration, of having fewer people ending up in local jails?

PICARD: Well, I think that they show fairly strong potential contingent on the stated goals of the jurisdiction, being decarceration at the time the risk assessment tool is implemented. Risk assessment tools themselves are agnostic on how the outcome is applied to practice and here’s-

WATKINS: They’re tools, essentially. They’re tools.

PICARD: They’re tools, they don’t foretell a particular outcome until the individual or group using the risk assessment tool shapes their use in order to reach a particular outcome. I do think that we see examples of this in practice right now.

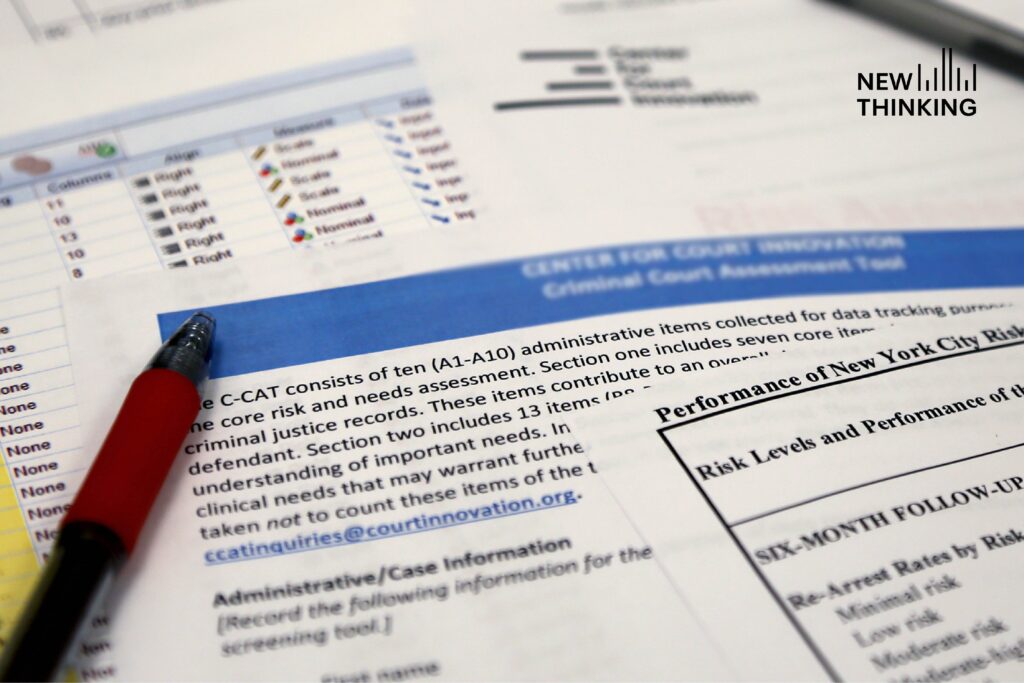

For example, in New Jersey, who’s had great success, I believe they’ve reduced their pretrial detention rate by 20 percent in one year.

WATKINS: And they’ve done away with cash bail altogether in New Jersey and replaced it with risk assessments.

PICARD: They’ve done away with cash bail and replaced it with risk assessment, not without controversy, but I think one of the unique aspects is that they were very explicit in their desire to reduce pretrial detention at least, if not incarceration overall, and that they’re only considering detention in the top 5 percent of the cases that they’re looking at.

WATKINS: The top 5 percent determined of risk level, you mean?

PICARD: Of risk level.

ADLER: I think it’s important to point out the fact that New Jersey is one of the few laboratories that we have right now to really assess both the potential gains and the potential downsides of risk assessment.

The truth is, in most jurisdictions, we don’t have a good enough example, that we can learn from and course correct. So, I think New Jersey is an important example because we have it as a proof of concept and we’re going to be learning a lot of lessons from New Jersey that, hopefully, will improve our implementation efforts across the country.

WATKINS: But we do have entire states right now that are using risk assessment, right? We have New Jersey, Kentucky… California is gearing up for it. We have jurisdictions across the country using risk assessment, so it’s not only theoretical. Sarah’s made the point that there’s no guarantee that you implement risk assessments and therefore you see your detention numbers go down.

New Jersey’s one example. Are there other examples that are maybe less promising for the effect on decarceration?

PICARD: Yes, I think there are. We also have examples where primarily due to the many challenges of implementation, risk assessments tend to be really good in theory, and maybe not as good in practice. That is not necessarily a criticism of the algorithm itself, but more a reality check on how difficult these kinds of big culture-change type reforms are.

WATKINS: We’re getting into this aspect that risk assessments are tools only, but they’re implemented by humans, fallible humans, and an entrenched culture. Justice systems tend to have pretty deep cultures and histories of practice, taking us into this favorite pet slogan of Julian’s that “culture eats strategy for breakfast.” This idea that you can come up with the best tool in the world, but it’s really about how it’s actually implemented and how it’s actually used.

ADLER: I think the challenges of implementation are enormous. In most jurisdictions, when we’re talking about criminal courts, there’s something practitioners refer to as the “going rates.” Meaning there’s a sense defense attorneys and prosecutors and judges have about “what a case is worth”—based on the charge, based on the facts, based on the weight of the evidence, based on a defendant’s rap sheet, and other such things.

WATKINS: And that’s kind of instinctive, almost cultural, that assessment…

ADLER: It is instinctive. It drives both those rapid-fire arraignments that we described before, as well as the far more frequent informal way that criminal cases in the United States are decided by plea bargain.

The point being that if you’re going to, as a reformer, look to use a risk assessment tool to appreciably change pretrial decision-making and use of jail, you’re going to have to find a way to renegotiate the going rates, both as a paper exercise, as well as working it into the fabric of instinctual, into the DNA of, lawyering in that jurisdiction so that lawyers and judges understand what a risk assessment score or category actually means in practice.

The challenge of rethinking, renegotiating the going rates based on risk rather than based on some combination of law, fact, and local professional culture is incredibly difficult to do. It’s not the clearest thing to organize. It can’t just be a series of meetings. It really goes to the way that practitioners are socialized to think, and act, and justify tough calls in a hothouse, fast-paced criminal court environment.

WATKINS: But I imagine some of the pushback from judges, from prosecutors that we’re calling cultural, some of that pushback has to be based on saying, “Hey, I don’t really want an algorithm making these decisions for me.” And a kind of revolt of the stomach against the idea of having a machine, so to speak, making these consequential decisions as opposed to a human with their years of experience in the system.

As a way of turning to look a little bit at some of the most prominent criticisms of risk assessment, could we talk a bit about how risk assessments are making decisions about individuals that are very consequential but that are not tied to that individual, per se? It’s a decision about an individual but based on an enormous dataset, say, of the previous 200,000 people who’ve passed through that system. Is that really a conception of justice that we’re comfortable with?

PICARD: Well, I think that’s an excellent question and I think to your earlier point, there’s often, especially by people who are making these decisions all day as opposed to planners or reformers who may be trying to work with them to make change, that the imperfection of these tools is very consequential and that they feel there’s so much left out of the tool that’s important to decision-making that they know, based on their own experience, that it makes the tools less trustworthy in the eyes of the people who most need to trust them.

I do think there’s that natural mistrust of the algorithm versus the human decision, although I think quite a lot of research in the social sciences, not just in the field of criminal justice but in other fields, shows us that when decision-makers take these tools as tools and not as a replacement for their own decision, that the decisions actually improve in terms of their accuracy.

ADLER: What’s interesting about the question is, whether you’re for or against risk assessment, there are two mythologies to be debunked.

The first is this idea that it’s risk assessment or a judge making a decision and that there’s no jurisdiction, including New Jersey and other states and jurisdictions that are very committed to risk assessment, that mandate judges to make decisions based on the risk assessment. We’re not talking about a situation where judges lose discretion. The idea is that a risk assessment can temper, inform that discretion, but not usurp that discretion.

The second is the idea that judges, even though they’re making decisions based on a particular case, aren’t using their experience of prior cases and people to inform those decisions, particularly when they need to make them quickly.

The point being that yes, risk assessment tools use aggregate data to make predictions about individuals, but if we’re really searching about how human beings attempt to make predictions about what people will or will not do, they’re doing something similar. It’s certainly not by way of algorithm per se, but I think, whether you’re for or against risk assessment, I don’t think either of those arguments really hold water.

WATKINS: Another major area of controversy, another argument brought up against risk assessments is this issue of transparency, that a lot of risk assessments are, if I’ve got this right, put together and marketed by private companies, and their formula, their secret sauce, is proprietary. It’s hidden. It’s behind a black box. So, defendants and their attorneys don’t actually know what’s going into the risk score that’s being assigned to them that’s then influencing a judge’s decision.

Sarah, could you talk a little bit about this issue of transparency and where we, at the Center, in terms of our interest in risk assessments, come down on that question?

PICARD: Yeah, I think that this is a major component of the debate about risk assessment, which has little to do with the accuracy of the risk assessment or some of the other controversies around risk assessment, that in our justice system and in order to assure due process, all parties should understand how decisions are being made.

I think the field has moved quite a lot on this issue already. I think five, ten years ago, many of the risk assessments that were used in practice were, as you say, not transparent and the algorithm could not be understood by the defendant. This has actually led to several court cases, none of which have spelled the end of risk assessment, but I do think they have served to push the field towards transparency.

Our position at the Center has always been that transparency is a key priority, for risk assessment practice and without transparency, it can’t be successful.

WATKINS: All right, I think I’ve saved the biggest controversy of all for last, and that’s the relationship between risk assessments and racial bias.

Proponents will say that risk assessments really have the potential for getting racial bias out of the system, but there’s plenty of evidence that it is in fact not so simple at all to do that. I guess Sarah, if you could just walk us through a little bit, this debate over risk and the effect, pro or con, on racial bias in the system?

PICARD: I think that at the heart of the debate, we’re asking ourselves—because racial disparities in the criminal justice system predate risk assessment—how the fact that we have historic bias running through our system intersects with these tools which rely on factors such as criminal history and sometimes socioeconomic factors in more complicated tools.

Critics, going back to 2014, Attorney General Eric Holder, have been concerned that some of these seemingly objective factors were in fact standing in as proxies for race. For instance, you see in many jurisdictions that people of color will typically accumulate longer criminal justice histories, not having to do with any individual propensity for crime, but partly having to do with socioeconomic factors or policing and criminal justice bias factors. I think this is the heart of the critique.

One thing that we found in studying risk assessments and developing and testing risk assessments is there’s a bit of a quandary where you can develop a risk assessment tool that will in fact predict accurately across racial groups. So, for instance, it will predict re-offense for a white individual as well as for a Hispanic individual and just as well for a black individual. However, individuals from certain groups may be more likely to fall into higher-risk categories.

This tendency for risk factors to be correlated with race may affect outcomes. You may have a racially neutral tool, yet still, you may have disparities in the outcomes that a risk assessment produces. For instance, the individual is high-risk and therefore they’re a candidate for pretrial detention. You may find that in some jurisdictions, African Americans are more likely to fall in high-risk categories and more likely to thereby be exposed to pretrial detention.

This is not a criticism of the algorithm itself, which is accurate for African-American defendants, but it’s a reflection of our reality where African-American defendants, for a variety of socioeconomic reasons, may be more likely to become justice system-involved, more likely to accumulate criminal histories, and therefore more likely to be in these high-risk categories.

WATKINS: It’s not a criticism of the algorithm itself you’re saying, because the algorithm itself is a prisoner of the data that it’s relying upon. And that data, in the form of hard numbers, looks very objective, but what we’re saying is that, in fact, that data is produced by a very subjective system, that there’s human subjectivity in deciding who you’re going to arrest or how many police officers you’re going to put in a given neighborhood or who you’re going to charge if you’re a prosecutor. So that data looks objective but is produced by a subjective system. Is that one way of explaining the paradox?

ADLER: It’s the paradox and it points up the argument that when we debate risk assessment, particularly with respect to racial bias, we’re debating a lot of things. We’re debating policing practices, and prosecutorial decision-making, and a host of other factors that complicate both pretrial decision-making as well as whether or not risk assessment is the right strategy to improve pretrial decision-making.

I think that’s part of what makes the debate so complicated is arguably, risk assessment itself is a proxy and it’s a proxy for broader concerns about racial bias and disparities in the criminal justice system writ large.

WATKINS: All right, but do we have a message, I suppose, for practitioners across the country who are either already using risk assessments or are interested in using with the goal of reducing their pretrial population and they’re perhaps confused, perhaps alarmed about this question of the relationship between risk assessments and race. Do we have a message for them about whether we think this technology is retrievable from that perspective?

PICARD: We definitely have principles for using these tools that are more likely to lead to success and less likely to lead to some of these unintended consequences. I think revisiting the idea of what are the values of the jurisdiction before they begin risk-based decision-making, what is the outcome we are trying to get to before we adopt a risk assessment tool. And not believing that the risk assessment tool is itself going to bring the outcome that’s desired. So, if the outcome is decarceration, if the outcome is greater fairness, then that’s the first step in successful use of a risk assessment tool.

ADLER: I think there are two questions that a well-intentioned practitioner needs to ask and answer as honestly as possible.

The first is how am I using risk assessment? We’ve discussed a range of things that we think can improve the practice. Transparency—so that if you’re using an algorithm that is not publicly available, either make it publicly available or change to a tool that can be made publicly available. Focus on judicious implementation—make sure that you’re renegotiating the going rates, that there’s a way to understand both the meaning and the implications of a risk assessment in the current system of deciding cases pretrial or at any other decision-point. And tracking outcomes with an eye toward reducing incarceration, if that’s a goal, reducing disparities, attempting to course correct when those things don’t appear to be going in the right direction.

But the more fundamental and the more challenging question is why am I using risk assessment? Jurisdictions that are committed to reducing the use of incarceration and are using risk assessment tools to reduce the use of incarceration will see greater outcomes and more success than jurisdictions that are using risk assessment for reasons that are less clear-cut or less committed.

Again, where this leads is less a question of what the data says or even a question about the technology. It really reduces down to values. What do you value? What are you trying to achieve in the name of justice? And what role does risk assessment play en route to that vision that you have?

WATKINS: All right. So, I suppose the question is where do we go from here? There’s a strong case to be made that the genie is out of the bottle with risk assessments. They’re now being used by jurisdictions and even entire states across the country. We’ve brought the case of the proponents, we’ve heard some of the criticisms, but do we have a sense of what the way forward is going to be?

PICARD: I think we have some sense that the way forward is to possibly pivot or to pivot away from asking whether we can immediately settle the debate on risk assessment, and rather, asking ourselves how we can accountably go about working with jurisdictions who are using risk assessment to inform the debate, and to continue to ask whether risk assessment tools can be used to increase fairness, to support decarceration efforts, and what that looks like.

So, I think we need much more open-minded examination of the practice in the field and a continued conversation, which includes both critics and proponents of risk assessment.

ADLER: I think it’s fair to say this is a liminal stage. It’s premature to settle the debate one way or the other. Moreover, as many jurisdictions that are using risk assessment are now lining up to use it, that we’ve seen that in the right place at the right time with the right people in the right roles, risk assessment can be used to reduce incarceration, we’ve also seen that risk assessment can be used in other ways and that it doesn’t guarantee one particular result or one particular outcome.

It would arguably be irresponsible to abandon risk assessment in the sense that we would stop trying to improve the science, improve the practice, and support practitioners who wish to both reduce incarceration as well as mitigate racial bias and other biases that interfere with what we consider due process of law and the fair administration of justice.

But we need to remain vigilant, we need to take the debate, especially the criticisms of risk assessment, to heart, and we need to be open to the fact that the practice can and will evolve before we reach a place of either adopting it full-scale and full-bore, or as Sarah says, pivoting to another strategy or set of strategies aimed at decarceration and racial equity in the criminal justice system.

WATKINS: Well, guys, I want to thank you both for being here today and for the work that you do on this subject. Thanks so much.

PICARD: Thank you.

WATKINS: I’ve been speaking with Julian Adler and Sarah Picard. Sarah is a Research Director here and Julian is our Director of Policy and Research.

You can find more information about this episode, including suggestions for further reading, at our website. That’s courtinnovation.org/newthinking. Technical support today provided by the collegial Bill Harkins. Our theme music is by Michael Aharon at quiverNYC.com. Samiha Meah is our director of design. Thanks also to our show’s founder, Rob Wolf.

This has been New Thinking from the Center for Court Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins. Thanks for listening.