To have an ability to be part of culture, when we have been purposefully separated from culture, is a big thing.

Books can be transformational, maybe nowhere more so than behind bars.

But the walls we erect around people who are incarcerated also disappear them from conversations about culture, politics, history—conversations to which they can make vital contributions.

The Inside Literary Prize is rebuilding those connections by celebrating the power of reading—and readers—on the inside. It’s the first major U.S. book award to be judged exclusively by people who are incarcerated. It’s organized by Freedom Reads, the National Book Foundation, and the Center for Justice Innovation, with support from bookstore owner and podcaster Lori Feathers.

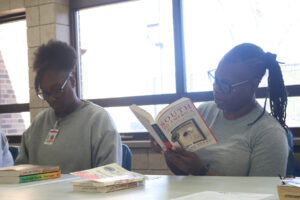

More than 200 judges across six states have spent months reading, discussing, and voting for the first winner of the award among the four nominated books. In this special episode of New Thinking, hear a behind-the-scenes portrait of what a day of judging sounded like in Shakopee women’s prison in Minnesota.

Photos courtesy of Freedom Reads.

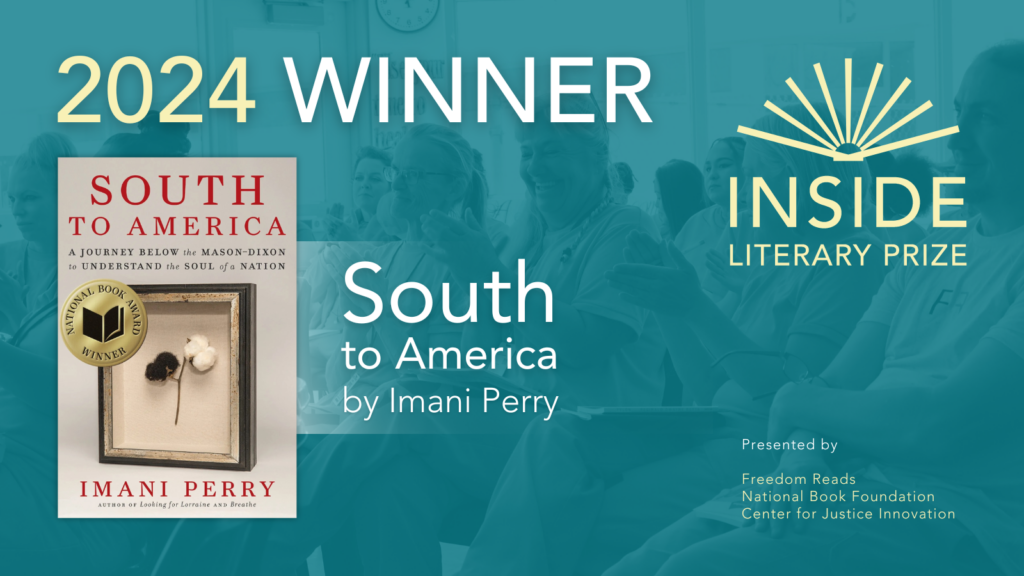

The Winner

South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation by Imani Perry was awarded the inaugural Inside Literary Prize. Read more.

Hear from Freedom Reads founder and CEO Reginald Dwayne Betts, and from this year’s winner on our Inside Literary Prize bonus episode on the New Thinking podcast.

Update as of August 14, 2024

The following is a transcript of the podcast:

Matt Watkins: Welcome to New Thinking from the Center for Justice Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins.

Books can be transformational, transporting. Maybe nowhere more so than behind bars.

But the walls we erect around people who are incarcerated also disappear them from conversations about culture, politics, history—conversations to which they can make vital contributions.

A new national literary prize is trying to re-connect those conversations and celebrate the power of reading—and readers—on the inside.

The Inside Literary Prize is judged exclusively by incarcerated people. It’s the first such large-scale effort in the U.S. It’s a project of Freedom Reads, an organization which confronts what prison does to the spirit, opening libraries behind bars; also the National Book Foundation, those are the folks behind the National Book Awards; the Center for Justice Innovation; and Dallas bookstore owner, Lori Feathers.

This is the prize’s inaugural year, with more than 200 judges in 12 prisons across six states.

In the background, you’re hearing judges gathering in the library at one of those prisons: the women’s correctional facility in Shakopee, Minnesota. In today’s episode, you’re going to get a behind-the-scenes portrait of what that day of judging and discussion sounded like.

Four books were nominated for this year’s prize by a committee of incarcerated readers, writers, and Departments of Corrections librarians. The committee was selecting from the list of finalists and winners of the 2022 National Book Awards.

And I’m going to tell you a bit about each of those four nominated books as they come up in this episode.

But right now, all 22 judges are assembled in the prison library, ready to make the case for their picks. So let’s get to our day of judging, and our day of voices from the inside, in Shakopee, Minnesota.

Steven PARKHURST: My name is Steven Parkhurst. I think I was on the Zoom with most of you, all of you. Freedom Reads tries our best to never go into a prison—since I’ve been on the team, 16 months now, we have never went inside a prison and introduced anything, unless it’s through somebody that’s been formerly incarcerated.

So, the thing that I share with you is that I’ve served time, and I’ve been in your shoes. And I served seven days short of 30 years… [exclamations from group]

WATKINS: Sixteen months ago, Steven Parkhurst was on a life plus 45 plus nine year sentence—no hope of release.

Then, he got parole.

Today, he’s back in prison, but with a visitor’s pass.

And a mission.

PARKHURST: But to be here? Stuff you all are doing here today, it should be from the rooftops and the mountain tops. People should know about that.

WATKINS: Whoever wins this prize, he says, that’s a big-time honor. But the prestige is in this room.

PARKHURST: It’s actually the first-time effort anywhere in this country. Let that sit there for a second: first time anywhere in this country that books are being judged by folks on the inside—who know a thing or two about books!

I let people know all the time, which your librarian is not shy about saying: people in prison, particularly women in prison, are the most well-read people in this country—period.

There is a couple of Ph.D. folks on the Freedom Reads team that I say, “you all ain’t got shit on what you read versus what people on the inside have read. You’ve read some different books but don’t start talking numbers because you’ll get embarrassed.”

WATKINS: It’s early morning, almost everyone is in baggy, prison-issue gray sweats, but expectation is coursing through this group. That, and something you don’t always get to feel in prison: pride.

HEATHER: I’m Heather. I feel super honored to be a part of this. Probably the biggest reason is, if I’m being honest, I have a lot of opinions.

And for the first time really—in my life—I have an opportunity for my voice to really matter. So, thank you.

WATKINS: Learning from, and maybe even getting to know a little, the people we lock away is the guiding motivation for what’s planned to be an annual national prize.

So I want to play those voices for a while now. This is about eight minutes of some of the judges introducing themselves as we go around the table.

And a few notes: You’ll hear the term “kite,” that’s what letters are called in prison, also “seg” and “LOPs,” meaning segregation and loss of privileges. Both are forms of punishment inside. You’ll also hear a lot of references to “Ms. Smith.” That’s Andrea Smith, sitting at the table with the judges here in the library. She’s Shakopee’s long-time and clearly beloved librarian.

CHELSEA: I’m Chelsea. I joined because reading is my life. The library is my happy place. And I remember our last Freedom Reads circle and Ms. Smith announced the literary prize thing, and I skipped over all the book circle answers and went to the last page to find out about this. Because I was like, “Wait, what? I can judge something, and we get to meet in person? Like, wait.”

And so right away I was like, “I’m in. Put me down.” And I had all these things going on and I was like, “Ms. Smith, ignore all that. I got this.”

I’ve always been a big reader. But then I had kids, and I stopped. And then I got incarcerated, and I’ve been incarcerated a little over four years now. And in the last four years I’ve read over 550 books.

So I mean, reading is just, it’s my escape. So, getting these four different books, being able to laugh at some of them and being able to cry through some of them, I just love it. And being able to have something that one day I’ll be able to tell my daughter, “I was a part of the first Inside Literary Prize judging. Isn’t that amazing?” So, yeah.

ALI: My name is Ali. I didn’t necessarily want to sign up, but I did. I didn’t realize how big of a deal it was at the time until we started reading and talking and just doing our book circles and talking about each book with one another. It brought out a community in here. So, when we can join together and bring different insights and opinions and voices to the table about one similar subject, it’s really uniting, and it’s just, it’s been an amazing journey.

DARNIKA: I’m Darnika. In prison and in real life I’m very soft-spoken, very standoffish, so this gave me a chance to just do something. And plus Ms. Smith is just one of my favorite staff, so I wanted to give back in participating with her. But I really do just love reading all kinds of books. I am not really a specific, I just read everything.

This is my first time in prison, so it just takes me outside of here. But with these books, it was really good to read. It gave me something to think about and I really appreciate that, because in here you really just have nothing to talk about. So, this gave us something positive to talk about, something to look forward to.

So, I really appreciate being a part of it and it gave me something to be able to tell my nieces that I was a part of, so…

COTY: My name is Coty. Honestly, the thing that drew me to this in the memo was that I get to be a judge if I get picked. Like, how great? I get to be the judge this time!

FRENCHIE: I go by Frenchie. What attracted me to this is I’ve been locked up since I was 17, so I never got to vote. So, I was like, “Yeah, this my chance to be an adult and make a vote!” And it’s an opportunity that I took to read books that I don’t normally read. Because I can be a snob when it comes to books I read. Yeah, I’m definitely a book snob.

TERRA: Oh, I’m Terra. I’m just waking up. So I’ve been knowing Ms. Smith a while. And so with COVID we were doing the Freedom Reads. So, I really liked that and anything that has to do with her, I try to get involved in it because she’s super dope.

So, with this, I knew it was going to be challenging because I was in school, and it was because I would find myself trying to hurry up, get done doing my homework. Because I was into one of the books. I would try to prioritize my time: okay, at least 20 minutes when I wake up, 20 minutes before I go to bed, because I had so much homework…

KRISTI: Most people just call me Trisket. I really, really am honored to be part of this because Ms. Smith is big on “no seg, no LOPs.” And I went to seg right before we got to start this, and I begged her in a kite.

I said, “I’ve been doing the Freedom Reads thing for as long as I’ve been in here. And I really feel that, yeah, I know I messed up! But I feel like I go really hard for Freedom Reads and I belong to be in the book circle.” And she said, “Okay, I think you’re right.”

I really love books. I read about 185 books a year. I go to MSU, so I have not very much free time, like what Terra was saying, but I always make it a point to read my books. And I probably read my books more than I do my homework. But that’s because when I read a book, I can get into it and it’s an adventure for me. An escape that’s not drugs, and it’s awesome.

I read and I write. I just got one of my pieces published in the River Whale Review, so that was super awesome for me. And I just really love reading. I love words. I love words.

RYAN: My name is Ryan. I don’t really like talking in groups and I’m not much of a joiner, but I do like to read. I have learned that I am more of a my-genre kind of person—I had a really hard time getting through some of these—but it was nice to learn stuff.

PARKHURST: What’s your genre?

RYAN: I like love. I love love. [laughter]

BRYN: Hi, I’m Bryn Montello, and I just want to make it clear you can put that name anywhere—because the number one thing that I want to get out of this is a job. I have always been very vocal about saying that: to have a different face of incarceration for the rest of the world.

For people to see that we are people that think about the books our children are reading and we spend time on the phone to try and share our love of reading with them. Or some women are trying to broaden their abilities in reading in order for their children to have different sets of circumstances with education and things like that.

But we’re trying to fight for spots to be able to go to college. Some of us are two or three credits away from a degree. And the difference that things like this can make in how people see us and are willing to put us in places to continue to educate us, to give us jobs. Because to have an ability to be part of culture when we have been purposefully separated from culture right now is a big thing.

Ms. Smith has saved many of us from wasting away—not getting too broad in our minds when we’re in here. I’ve said it many times before, throughout the 10 years unfortunately, that I have been here, in and out and in and out.

WATKINS: Those are some of the voices of the judges for the Inside Literary Prize at Shakopee women’s prison in Minnesota.

And let’s hear now from the much lauded Andrea Smith, the prison’s librarian for 19 years.

Smith says books can be transformational behind bars, just like building relationships can be. At its best, this prize is doing both. But prize or not, someone on the inside needs to advocate for culture, for community. That’s how Smith sees her role.

Andrea SMITH: I’m often talking to the women, like, this is life too. These years count too. We’re doing stuff together: you matter to me, you matter to other people, this counts. So, I think the advocacy piece is the reminder of… just dignity and humanity, and once you feel secure and safe in that you can pursue other things, you can try new things, you can sign up…

Like there’s a couple here that, they don’t sign up for anything, ever! But they feel safe enough to sign up for this. And I don’t know what they’re getting out of it except that they showed up. It’s that whole thing of: if they didn’t want to be here, they wouldn’t.

So, it says something to me that they’re here, and if they don’t say anything, like, it may not be about me, it’s because they’re here with another person that they enjoy who reads alongside them or maybe encourages them. It’s that community aspect that matters, that I think library can be the bringer of that, the ship of that, whatever metaphor you want to use. But it’s the space that we’ve designated that matters.

And in Minnesota, I’m just really happy that all of our facilities have libraries and are staffed and do care. And it’s not something we’ve had to argue about. It’s just something the state believes in and that’s a relief, because then you can just do the work of being around people. So much of the work—all of my friends are public librarians, obviously—like, you pay me to hang out the people you don’t want to hang out with! That’s the job.

WATKINS: About a third of this library we’re talking in is given over to a children’s play area. It’s a place for kids and moms to be together on visiting days. There’s a colorful carpet, animal chairs, shelves of kids’ books. It’s good to see, but it also breaks one’s heart a little.

I ask Smith about the effect of being separated from kids and family.

SMITH: Yeah, I think you see that considerably more in women’s facilities, where kids are always in the room, even when they’re not in the room. We talk about that a lot and the library collection reflects that as well. And the other thing…

What I observe a lot is that the women spend a lot of time trying to understand the decisions that came before or trying to understand childhood, because they have kids. They want something different for their children, so you have to understand your childhood first. And see what’s being replicated and what you can and cannot change—at a distance.

SOUND UP: Can we talk about The Rabbit Hutch for a couple of minutes? [sounds of general agreement, rustling of pages]

WATKINS: We’re in the thick of the judging session now. Up for discussion, is Tess Gunty’s nominated novel, The Rabbit Hutch. Ricky reads from a list of “life lessons” compiled by one of the characters.

RICKY: “And do not let your children become casualties of your own damage. And do not have children if you cannot ensure the above.” And I wish I would’ve did #22 before I damaged my children.”

So it’s like… There was a lot of them in here that touched home and this stuff that I would do. And I’ve been in a pretty dark place lately, and it’s made me laugh and kept my spirits up, and I even pick it up some days and read bits and pieces. So, this is definitely going to be my choice.

WATKINS: The Rabbit Hutch unfolds over the course of a week inside a low-income housing complex.

The story also touched home for Jamie.

JAMIE: The Rabbit Hutch I really liked because I like books that I can relate to. So, what Brandy said about how the teacher, well, when his wife was like, “Didn’t you see her?” Or, “didn’t you always meet her?” And he was like, “I never actually really seen her.” That really hit hard, I guess.

But just all of it altogether, because I too grew up in foster care and everything else, so I feel like I could see this whole life, because I always grew up on the streets and in out of foster care. This book was teenage more, because I could see the teenage me in this book—reliving it.

What happens when you—some of us—don’t have the right guidance, I guess.

WATKINS: Among the four nominated books, The Rabbit Hutch seems the easiest to connect to. The most difficult appears to be the book of poetry, Roger Reeves’s Best Barbarian.

Yet Reeves’ poems generated some of the day’s best discussions. And what becomes clear is just how much everyone has been talking about these books. Terra starts this off reading aloud Reeves’ poem, Cocaine and Gold. And you’re going to hear two excerpts from that reading.

TERRA: Literally the cocaine gold one, I read that poem like eight times! [laughter]

I was trying to figure out… I really want to know what he’s talking about! If that’s possible…

Gabrielle COLANGELO: Do you want to read it?

TERRA: Okay.

“I never wanted to be this far

Into the business of heaven

Chasing my father hunting

His soul in the corn and confusion of this harvest

My father who is hidden

In the last sheaf of heaven maybe

Heaven itself

My father the corn-wolf

Who we must kill but is already dead

We will learn nothing

Here of sacrifice or the cocaine.”

This is where I got confused.

[cross-fade into final section of poem]

Freedom without freedom

To hold your dying father up

To a razor beneath a golden light

And cut him finally in and out of the world.”

KATIE: I didn’t understand the entire book either, so you’re not alone, I promise you.

Bryn had to break down… I was in a discussion with Bryn. Ninety-five percent of that she had to break down for me.

TERRA: Oh, okay.

KATIE: Because I was like: “Where did you find that? Where did you get that?” Because I didn’t get any of the stuff that Bryn got.

TERRA: But what did you get?!

BRYN: I think that discussion was a fantastic discussion…

KATIE: It was!

BRYN: …and several people read things out loud. And I think the thing with this book, personally, we didn’t get to talk about it enough.

And I loved what you said just now when you said, “I’m going to keep going with this.”

So, personally, in ‘Cocaine and Gold,’ I think you’re exactly right. I think it’s about his father’s funeral.

I think it’s about when we eulogize someone, we use a razor and we cut out pieces of what their life was really about.

You’re not going to talk about the fact that his dad was probably—I’m guessing, from some of the references—on cocaine binges throughout a lot of his life and not around.

ALI: Honestly, one of my favorite discussions was on this book, because of us breaking it down, and there’s so many different perspectives.

So, what I got from the ‘Cocaine and Gold’ is I correlated, like, he’s talking about his father who was a drug addict. When you said razor blade, I automatically thought that’s probably what he did to make lines or whatever.

So he used something that was part of his father’s addiction to finally sever him from his addiction because he died.

The different perspectives, I feel like one poem doesn’t necessarily mean just one thing.

WATKINS: A strong contender for the prize appears to be Jamil Jan Kochai’s collection, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories. It’s 12, at times, fantastical stories about war and family set in modern-day Afghanistan and among the Afghan diaspora in the U.S.

Here’s Ali and Katie.

ALI: I loved The Haunting of Haji Hotak. That is my favorite book. If I don’t get into a book in the first ten pages, I’m out of it. But it’s a bunch of short stories. It made it fun. It made it fun. And even though some of the short stories were like, “oh my gosh, this is horrific.”

Like… Oh, what is it called? The one… ‘Return to Sender.’ That one was gruesome. But it’s like, wow, stuff like this actually does happen in real life. It rips off the, like what you were saying, the face of this stereotype.

KATIE: I totally agree with what Ali said because yeah, this book, within the first couple of things, I was just hooked. I was like: this is some twisted stuff. Like, I don’t know what’s about to happen next, but I had to keep reading just to find out how much crazier things were about to get.

But I definitely loved when he didn’t have a lighter and he just ate the Kush, and I was like, bro, I’ve been there. I’ve been there. That shit is not good, but I’ve been there.

So immediately I was just like, yep, I understood.

WATKINS: Two of the judges sitting around these tables are in well-pressed military-type uniforms. Brandy and Jackie are part of an early-release program called CIP. It’s like boot camp. Here’s Brandy then on why she’s voting for Haji Hotak.

BRANDY: So again, I’m Brandy, and for me, it’s this one for sure, the Hotak one. Because I’m in CIP, we’re not allowed to read personal books until 8:30 at night, and we literally get a half hour.

So, I hope none of the staff hear this over there- [laughter]

But I would sneak-read this book because it grabbed my attention that much. So in between classes, I would pick it up real quick, read a couple pages, put it away. I even got a little more sneakier with it, and I would put, like, a treatment book around it and pretend that I was reading the treatment book.

So, yeah, I’m telling on myself right now. It’s okay.

And I liked it so much that—I know I’m weird—it made me want to eat grass once. [riotous laughter]

I did try it. It’s not bad. Because I was thinking about the soldier that got put in that hole or whatever [all: “yeah”], he was eating grass with the goats and stuff, so I was like, hmm.

And then it makes me also want to pick up the Quran. I read my Bible, my Christian Bible, every night. But this made me want to look at the Quran, for some reason.

And I’ve cried in this book. I laughed in this book. So, if you can make me go through a rollercoaster of emotions with the book, I think, yeah.

So this is definitely going to be my pick.

WATKINS: The idea of the prize was never to generate a consensus pick, and that isn’t what’s happening in this room. Imani Perry’s South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation, won the 2022 National Book Award for nonfiction. And it’s the last of the four nominees you’re going to hear discussed.

It’s a meditation on the South, race, and America writ large.

It’s also got Rochelle’s vote.

ROCHELLE: South to America was my pick. [murmurs of surprise] It was a book that made me look at my preconceptions about the South, and there were so many things I didn’t know about the South.

I didn’t realize that there were so many people that fought against Jim Crow, against slavery, against all the awfulness that the South is known for. To make me change my mind on the South is a big thing. So, it’s definitely going to be my pick… I think it raised awareness of a lot of things that people should know and don’t.

WATKINS: For Heather, The Haunting of Haji Hotak was a book she loved. But her vote is going to South to America.

HEATHER: Going back to your question originally which: what makes a book good and that what makes it for this award? And I really had to think about that.

My final choice is this one. And the reason why, yes it was hard to get through, but it said things in here I didn’t know how to say, and I’m a writer.

When he talked about the George Floyd situation at the end, or when she talked about it, it just blew my mind. And she talked about, and I can’t find it at the moment, but she talked about the media and how the media portrayed him. And I don’t know anyone in here who hasn’t experienced that. But you tell someone on the outside the media lies, they’re like, “Oh, yeah.” And yet you’re watching it and not considering that it’s a lie.

Maybe this wasn’t the funnest book to read, but it was the most important.

TERRA: Yes, it was.

HEATHER: Talking about the man who, I can’t remember the part, he had five consecutive life sentences for something he didn’t do. And this is back in a time when… I mean, even worse than they are now, were targeted, that particular group of people.

And it’s sad that it happened. It’s so sad. But it kind of in a way, it gave me hope, because he does get out. And myself who doesn’t have a release date, I was like, everyone who’s telling me, “Look at all these people that don’t get out.” “Okay, but look at the person who did against all odds.”

And then he talked about when he was in segregation and how he handled that. And we each take something. He took the little pieces of toilet paper, and he laid them on him like a blanket. And I thought, “oh my God, each one of us have had a moment like that.”

Yes, we all have blankets, but how many of us take that imaginary stuff, which we probably shouldn’t say here, but the things that we use differently than how they’re intended in order to give us that piece of home and hope in the worst moments? And I connected so deeply on that.

So this has to be read.

WATKINS: Perry’s book teems with stories. In declaring her vote, Terra picks up on one of those.

TERRA: This is such an uncomfortable subject to even talk about, especially in a place like this, when people of my complexion, we live it. I actually had to get myself ready to read this book.

But what I really like about our ancestors back then, one of my favorites was Benjamin Banneker, and I say that because this dude, listen, the way he uses his vocabulary, and I just liked the way he so eloquently speaks.

So, I just wanted to read what he was talking to Jefferson, his response. He said, “I suppose it is a truth too well attested to you to need a proof here that we are a race of beings who have long labored under the abuse and censure of the world.”

And I love the way he uses his words: “…that we have long been looked upon with an eye of contempt and that we have long been considered rather a brutish than a human and scarcely capable of mental endowments.”

And I stopped there, and I was like, “Wow, I wouldn’t use that type of terminology.” And can you imagine back then… And then he was like, “Now, sir…”

Because me, if I’m going to be going crazy, I’m just going to say some stuff, like, “And you: da da da da da.” But the way he uses his tone. Listen, he was like, “Now, sir.” Okay, that’s respectful, right?

I just love the way he said that because it gives me that sense of: I like how you’re telling him in such a way that we are the same kind of people, and that’s just so powerful to me. So, I hold onto that. If you want to be racist, be racist, that’s fine, because I can’t change how you feel about that, but it just makes me feel so powerful that he was able to convey this to this man.

This is my pick for sure, not because she’s Black. This woman is… She’s brilliant.

WATKINS: After about two hours of discussion, final ballots are cast. And after that, the judges have some questions for Steven from Freedom Reads—you’ll recall he introduced the day.

You just got out 16 months ago, Brandy says to Steven. Now you’re flying around the country, meeting new people every day. That’s got to feel great.

PARKHURST: The great feeling is… I know there’s a variety of sentences in this room. I went to a teen drinking party when I was 17 years old that got out of hand. And I was sentenced to life plus 45 years plus 9 years.

So, I didn’t know when I was going to die but I knew exactly where I was going to die. And I sit here right now serving two paroles: one in Rhode Island and one in Connecticut, on them sentences. I am here on a very, very detailed parole work permit, travel permit, to be here today. I jump through every single flaming hoop to do this work.

Yeah, I’m grateful. I’m grateful but also, I’m an example to anybody in this room that is serving a lengthy sentence that I never thought in a million years that I would have a chance to come home, let alone be inside of prisons again doing this work.

This is the twenty-fifth prison that I’ve been in since I’ve been home. I’ve been in over 190 housing units, speaking to folks, since I’ve been home.

For anybody who believes that tomorrow never comes, or that the sentence is insurmountable, things change every day. So keep doing that work, keep showing up.

WATKINS: Talking to Steven after, it’s clear how galvanized he was by the day. These women, he says, they want to be judges, they want to vote, they want their voices heard. Books, this prize… they can be a vehicle for that.

PARKHURST: Reading a book says something about your character. It’s showing the world that folks on the inside do more than just gangbang, sell drugs—shanks, and whatever stereotypes are around. It’s not all Orange is the New Black or Oz or whatever stereotypes are around about prison.

These are the most well-read people in the world, and that’s what I would want to be recognized for, if someone was going to talk about a prize and publicize that. I read books in here and I try to get better, I try to be better and try to do better.

SOUND UP: Randall Horton book signing: “Hey, my name is Ali, A-L-I…”

WATKINS: It’s the afternoon now in Shakopee. Russell Horton is signing books after a reading he did before a packed library. The Freedom Reads event was open to the whole prison. Horton is a formerly incarcerated tenured academic and award-winning poet.

Like Steven, he spends a lot of time now returning to prisons. He’s not nominated for this year’s Inside Prize, but I asked him: what would it mean to a writer to win this thing?

Randall HORTON: I look at it as a huge honor, and I think a lot of them view that as a huge honor to be acknowledged by those inside the carceral state. Because, A: it’s already widely understood that it’s a very reading population, but more so than that, it just gives you a certain sort of credibility outside of that whole literary community, you know what I mean?

It’s almost like a people’s award, really it is. And for me, I couldn’t think of any honor more prestigious than that. You’re being recognized by one of the most invisible populations within the United States, but they also going to bring it to you real.

WATKINS: Books are about bringing us closer to other people’s experiences, their perspectives, their humanity.

But along with all of the gratitude I heard from judges over the course of the day—grateful for this prize, grateful even for this podcast—there was a note of surprise. People on the inside don’t expect the world on the outside to acknowledge their humanity.

And that is everyone’s loss.

Here is Lee, reflecting on what the day of judging, and this prize, have meant to her.

LEE: I’m super happy to have this opportunity, though. I know when it came out, we were the first inside, I was like, “They care about what we think?”

HEATHER: Right!

LEE: I was like, “What?” I was like, “This is the first one…” And they actually care. They want to hear about what we think, the ones that they have shut away. And so it mattered. It really mattered that people cared, and that they wanted our input, wanted to see what we thought about the books that they chose. So that was really shocking, and I felt really honored. I’m really honored to be part of this.

WATKINS: That was our documentary: ‘Inside Literary Prize: Shakopee Women’s Prison.’

And it’s dedicated to all of the more than 200 judges across the country who made this year’s prize happen.

Now, the winner of the Inside Literary Prize is being announced just a few hours after this episode is released. To find out which book won, click the episode page link in your show notes, or go to our website.

And on that same page, you can see some really great photos from the day in Shakopee and there’s a full episode transcript.

There are a number of thank you’s to make for this episode: first and foremost, to the women at MCF-Shakopee and to your librarian, Ms. Smith: deepest thanks for your welcome and for your words.

Then: Steven Parkhurst and Gabby Colangelo of Freedom Reads. Thank you for taking this podcast under your wing so generously during our days in Minnesota.

Next up, our partners in this Inside Prize effort: much gratitude to everyone at Freedom Reads, at the National Book Foundation, and to the unmoved mover in all of this: Lori Feathers.

At the Center for Justice Innovation, many thanks to Julian Adler and Josh Stillman. And to the entire communications team here: Dan Lavoie, Emma Dayton, Bill Harkins, Samiha Amin Meah, Michaiyla Carmichael, Catriona Ting-Morton, Daniel Logozzo, and Elijah Michael.

And some personal thanks to Vivien Watts, Emily Watkins, and Roger Picton.

Today’s episode was written, mixed, and produced by me. Samiha Meah is our director of design, Emma Dayton is our V-P of outreach, and our theme music is by Michael Aharon at quivernyc.com.

This has been New Thinking from the Center for Justice Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins. Thank you for listening.