We believe that the closure process is only going to be realized if we sustain organizing, and increase that organizing over time, until the last person is taken off that island.

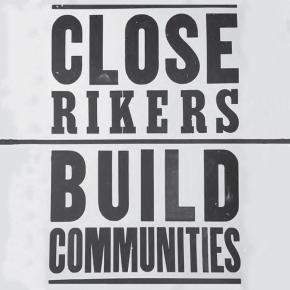

gabriel sayegh addresses a #CLOSErikers rally

The movements to end cash bail and close local jails are tightly connected—less use of bail means fewer people detained awaiting trial and that makes it easier to shutter the institutions used to hold them. In New York, gabriel sayegh, the co-executive director of the Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice, is in the thick of organizing both fights.

Advocates and senators celebrate the passage of statewide criminal justice reforms in April 2019

In New York State, sweeping restrictions to how bail can be used are weeks away from enactment. Assuming it’s implemented correctly—a considerable assumption, sayegh points out—our own research estimates 90 percent of cases currently eligible for bail, and hence pretrial detention, will no longer be eligible for either come January 1, 2020.

sayegh, whose group has been one of the leading organizers of the bail campaign, calls the legislation “arguably one of the biggest pretrial reform packages that's passed," not only in New York, but in the United States.

Indeed, the anticipated effect on jail populations is part of what is making it easier for New York City to move forward on its promise to close the notorious Rikers Island jail facility. Katal was one of the founders of the movement that helped to secure that improbable promise. Now, sayegh says, the focus has to be on ensuring the city follows through, and on improving the plan laid out for the replacement facilities intended for a fraction of the population Rikers held at its height.

Resources and References

- Analyses of New York's 2020 bail reforms from the Center for Court Innovation, the Vera Institute of Justice, the Data Collaborative for Justice, and Katal (parts one and two)

- 'Making Sense of the Fight Over NYC Jails,' sayegh parses the multiple post-Rikers plans and lays out the stakes (10.19)

- The split on the left over after Rikers: Melissa Gira Grant in The New Republic on a "conflict...rooted in broad agreement," and Anakwa Dwamena on the "competing visions" in The New York Review of Books (10.19)

- Katal's reflections on the "first two phases of #CLOSErikers," 2015-2017 (01.18)

- New York City's Mayor's Office of Criminal Justice revises its expected jail population downward—again (10.19)

- The New York Times on "the boat," the Bronx's floating jail barge (10.19)

- 'New Funding for Pretrial Services Agencies Left Out of NY Bail Reform Law,' New York Law Journal (04.19)

- The Marshall Project on how changes to culture, not legislation, are already driving down the use of bail in New York City (03.19)

- 'The "Failure to Appear" Fallacy,' The Appeal (01.19)

- A seminal New York Times investigation into New York's upstate "town and village courts" (09.06)

The following is an annotated transcript of the podcast:

Matt WATKINS: Welcome to New Thinking from the Center for Court Innovation. I'm Matt Watkins.

Both elements of today’s title are aspirational: ending bail, closing Rikers—neither has happened yet. But some really significant progress is being made on each.

In New York State, sweeping restrictions to how bail can be used are about to be enacted. It’s maybe the most significant of any of the statewide bail reforms passed so far. Assuming it’s implemented correctly, and we’re going to get into that, my colleagues here estimate 90 percent of cases currently eligible for bail—and thus pretrial, or wealth-based, detention—will not be eligible for either come January 1.

Then, on closing Rikers Island—New York City’s isolated and notoriously violent jail facility: as I record this intro, we’re just a couple days away from an historic New York City City Council vote. It would authorize the construction of four replacement, so-called community-based jails.

And in the handful of days since I recorded the interview you’re about to hear, the city has just lowered—yet again—its target population for those replacement jails. You’ll hear some talk in this episode about jail numbers, and getting them down as low as possible, so bear in mind the planning now is for a New York City-wide jail population of 3,300 by 2026, when Rikers is scheduled to be closed. I don’t think even a year ago anyone thought we’d be making plans based on so low a number.

The movements to end bail and close jails are connected and my guest today is in the thick of both those fights. gabriel sayegh is the co-executive director of the Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice. I started our conversation by asking him to tell me a little bit about Katal.

sayegh: We’re relatively new still. We launched in 2016. And we use organizing and advocacy to try to transform systems. We work with the people impacted by the issues that we're working on. So, when we work on bail reform, we working with folks that have been impacted by really terrible bail laws. When we're doing parole reform, we're working with folks that have been impacted by the parole laws.

We work on police accountability and arrest diversion—trying to keep people out of the system. And those are all really local fights. We also do state-level reform in both Connecticut and New York, where we're trying to connect the work locally with the work at the state level and vice-versa.

So as an example, when we started working on the Close Rikers effort in 2015, it was the first campaign that we had started working on in partnership with JustLeadership.

WATKINS: Even before Katal had publicly launched.

sayegh: Before we existed, before we'd finalized our paperwork, before we'd even finalized our name. It was the summer of 2015—my co-director, Lorenzo, and I in August of 2015 wrote the first strategy document for the Close Rikers campaign. And the Close Rikers effort has obviously distinct city-based elements here to close down that jail, but you have to do things at the state level to make that possible.

But that kind of connection—like, we want to do this thing in the city, which is close Rikers. To do that, we have to reduce the population in the jails, the detention population—we've got to get people out. There are some things that the city can do to accomplish that aim, but there are things that you have to do at the state level.

Our principle methodology is community organizing, and my co-director, Lorenzo, is a long-time organizer—25, 30 years. I've been organizing for almost 20 years, but he's one of the people that mentored and trained me along the way. But we don't leave other methodologies on the side. We utilize advocacy and communications. So, we try to find ways to bring together teams or partnerships that can do more together than any of us could do on our own.

WATKINS: This big package of criminal justice reforms that has recently passed in New York State that your group was involved in advocating for, it's got a few prongs: we've got discovery, we've got speedy trial. For the purpose of this conversation, we're going to focus mostly on the bail aspect, which I think is the one with the greatest potential—decarcerative potential—greatest potential to really reduce jail numbers.

So, let's just start with a 101 a little bit. The purpose of bail is to try to guarantee that people are going to show up for their next court appearance.

In general, why do people miss court appearances? And how effective is bail at making them show up?

sayegh: The first thing is people can miss a court date for any number of reasons, not the least of which is our justice system is Byzantine and completely confusing to the everyday person. It's confusing even to actors within it. You can be given a desk appearance ticket, miss that date quite easily, and all of a sudden have a bench warrant out for your arrest. It is easy to miss a court date, particularly for people who have lives that they're trying to live—to get their kids to school, go to work, and so forth.

Most people, if they have a court date, they want to go get the darn thing resolved and over with. It's a matter of making sure that they know when the court date is, and making the process clear for people so that they understand where they have to be and what time they've got to be there. And also, not being flippant with people’s time.

You go stand in line in court in the morning. You're there for a better part of the day waiting for your case. And then all of a sudden it gets pushed back again another six to eight weeks, and you've got to go through the whole thing again. This system just grinds people down.

And then of course what happens is that many people can't afford to pay the bail that the judges set. And that's when you see folks ending up detained because they can't afford to pay something, which is the heart of the injustice here in many respects, because if you've got the money, you can pay the bail, but if you don't have the money, you're usually sitting inside. Or you've got to work with some bail bonds company that-

WATKINS: A for-profit…

sayegh: A for-profit bail bonds company, where the bail fund is usually a nonprofit that will pay your bail. There's no profit motive there. Usually bail funds are oriented around trying to help people, and to transform the system and make it more just. Whereas bail bondsmen, or the bail bonds industry, is around extracting capital from poor people and getting themselves a profit from it. And so, for low-income people—which are the predominant number of people cycling through our system—the bail setup is egregious. It is patently unjust, and poor people all the time get stuck in jail simply because they can't afford to pay a bail, and that's at the heart of the problem here.

WATKINS: We know that the bulk of people in New York City, New York State, and across the country in local jails are there pretrial—awaiting their trials—generally because they can't afford their bail. A lot is at stake here. What do we know about the really negative effects of pretrial detention itself?

sayegh: Any time in jail is bad for people: people can lose their jobs, they can miss paying rent, not be with their kids. Health impacts of jail, even a short stay—the stay of a few days—are awful. They're only there because the court says, “well, the mechanism that we're going to use to make sure you come back to court is this money bail. You don't have that money, so to make sure that you're here for the court date, we're going to keep you in jail.” That's outrageous—just flat out.

And it harms people, particularly around mental health issues. Folks oftentimes end up having mental health episodes that get triggered as a result of their jail stays. They're violent places in many respects, in addition to many of them just being terrible places to be physically.

And anyone who's ever been to Rikers and walked through: it is an awful place. And the fact that people are there at all is a scandal in this city. The fact that people survive it is a testament to their perseverance and resilience. And the fact that the city hasn't shuttered the darn thing yet is really, shame on all of us, for that, as a city.

WATKINS: So, we're getting a good sense of the scope of the problem out there associated with bail and the way pretrial detention can function in this counter-productive way if the goal is producing greater public safety. If we turn to look at the New York State legislation, what's the significance for you of what has passed now with regards to bail. What are the biggest highlights for you?

sayegh: There are multiple things in this package that are worth talking about because it's arguably one of the biggest pretrial reform packages, and criminal justice reform packages, that's passed, certainly ever in New York, and also in the nation. It is extremely significant what New York has done here.

Jail populations—if this new law is implemented correctly—are going to drop precipitously, especially outside of the city of New York, but even inside of the city of New York. Some estimates, even the Center for Court Innovation’s estimate, is well over 40 percent.

WATKINS: Forty-three percent, I think, expected at Rikers.

sayegh: Yeah, will be the expected drop, which is significant here. There was another recent report coming out of a place at John Jay, one of their research institutes there…

WATKINS: Data Collaborative for Justice, I think.

sayegh: Yes, and they did their report that I was reading that showed that: if the bail law had been in place last year in 2018, 21,000 fewer people would have been detained. That's a lot of people not having to cycle through that system.

WATKINS: And they went back even through the broken windows era and ran the numbers…

sayegh: Yeah, they did like 10 years.

WATKINS: …something close to half a million.

sayegh: And then you think of all the money. I think their number for 2018 was how much bail got paid for those folks and I think they landed on about $200 million. And so that's $200 million coming out of low-income communities, communities of color here in this city, to pay bail…

WATKINS: Or the bail bond industry.

sayegh: Mostly to the bail bond industry—that's most of where that's going.

WATKINS: We should maybe just tell people what the changes are so they know what we're talking about.

sayegh: Yeah, the biggest of which is that there's a whole bunch of offenses now—misdemeanor offenses and some non-violent felony offenses—for which they have to let people go.

WATKINS: It's not like you need to consider this. It's now a clear mandate.

sayegh: They have to let people go. There's not a mechanism—with rare exception and technical things that I won't dive into here—they just have to let those folks go. And the rationale behind this, of course, is that: why are we holding people to begin with if there's no immediate or obvious threat to the public safety here?

And so, a significant portion of the people that are cycling through Rikers every year on these misdemeanor charges and non-violent felony charges will not be there anymore. You give them a court date. There's going to be some pretrial services that will help folks get back to court as they need to.

And then they also changed, as an aspect of the larger package, there's an element there that requires police to give people desk appearance tickets. This is also a huge change because this happens for a lot of the low-level offenses, particularly misdemeanors, where the police will no longer have the option of detaining those folks as they have been—bringing them back to the station, fingerprinting them, mug shot, holding them.

WATKINS: Holding them right through to arraignment.

sayegh: Right through to arraignment, that's right.

WATKINS: On a really minor…

sayegh: On a minor charge, and that's no longer going to be an option for them. So, these are major changes that are going to fundamentally alter the landscape of the pretrial justice process here in the state of New York.

SFX: music stinger

WATKINS: Another panoply of non-monetary release conditions involves supervised release. This notion of a really beefed-up pretrial services agency that is going to be assisting people who are released but helping them to get into services they might require, and helping them show up for their next court appearance. That seems like a big implementation lift in New York City, and even more so upstate.

Full disclosure, we're already at the Center for Court Innovation helping to run supervised release in this city. But what are you seeing there in terms of preparation for this big shift, especially upstate maybe?

sayegh: Down here in the city, the impact of these reforms will be significant, but the city is far more prepared to implement these reforms than are any jurisdictions outside of the city. There are two reasons for that. One is that you really do have two jurisdictions operating with really separate conditions here in the state of New York: you have inside of New York City and outside, and they could not be more different in many respects.

Those differences also shaped the reform process itself. We did a write up on this that folks can find on our website, if they're looking for more background: like, how did the reforms come about? What were the dynamics between advocates? Why did some advocates want one thing and others were pushing for others?

WATKINS: I'll put it on the episode page for this as well.

sayegh: Great. So, New York City is unique in the state and unique in the country. We've dropped the number of people in our jail system dramatically from a peak of 21,000 in the early '90s, down to 7,000—around that—today. The number of people New York City is sending to prison, state prison, has dropped dramatically. So, most of the people in state prisons used to be coming from New York City. That is no longer the case and hasn't been so for some time.

WATKINS: Right, now it's outside New York City that is driving incarceration.

sayegh: That's right, outside of New York City. And New York City has established a range of different programs and services that the ecosystem of reform here is just fundamentally different.

So, groups like the Center for Court Innovation, but there's a range of other groups as well, that are piloting projects, starting programs—alternative to incarceration programs, diversion, reentry programs. We probably have the most robust reentry apparatus here in the country, as well as probably the most robust ATI—Alternative to Incarceration—apparatus in the country. It's just different here in the city. The judges have culturally shifted much of what they're doing.

So, all this is to say we've made progress. It's not to say we've achieved where we need to be. We don't at Katal believe that, that's why we're continuing to work for reforms. But it is important to understand how far we've come here so that we can really begin to contend meaningfully with what we now have to do to get to a finish line down the road.

So those differences are going to shape how this thing gets implemented, and one of the biggest factors here, aside from money—which is a big one: the investments to make the pretrial services work, they haven't been done to the extent that they need to be.

WATKINS: There's very little new money, for upstate, for these pretrial service agencies, which in many counties and jurisdictions barely exist, or are run out of the probation department.

sayegh: Yes. But the other thing that's big is that as a part of that jurisdictional difference, the majority of the people that are currently in detention in the city of New York are there on felony charges, and out of that universe, mostly violent felony charges. Everywhere else in the state most of the people that are in the local jails are being detained on misdemeanor charges.

WATKINS: Awaiting trial on misdemeanor charges.

sayegh: That’s right. But this difference, you can't overstate the importance of this for implementation reasons, because the drop here in New York City and that shift is not just unique in the state of New York, it's unique nationally. There are few other places that have done that, certainly of the large jurisdictions. And there are few other places that have that makeup of a detention population that have also dropped the number of people it's detaining, or even bringing into the system, as much as New York City has.

This is important for implementation because it means that, culturally, actors in the system are more familiar and ready to do something like this, even if all the resources that are needed to do it aren't totally there yet. Now the state should put much more resources into pretrial stuff, and we think that there's a lot more that has to be done on the reform side to make that really clear.

WATKINS: And into training staff to change this culture.

sayegh: Exactly. But as a result it will look different in the city of New York. And in upstate, we're anticipating that some counties may even just flat out refuse to implement at first. The D.A.s are dragging their feet. Upstate elected officials from the legislature already want to change the law, as do some here in the city, actually.

So, this is going to be a political fight as much as anything else to make these counties follow through, but we also have to keep pushing the state to provide the resources necessary so that counties aren't going back to using jails as a mechanism available to them to bring people back to court because after January 1st, they won't have that option for most people anymore.

WATKINS: So, implementation, always this massive challenge when it comes to: you can craft legislation, but how it actually happens on the ground becomes this enormous issue. And we're just going to put a flag, then, in this fact that upstate, or basically everywhere outside of New York City, is a real concern when it comes to implementing this law.

But if we look at this reform itself, it's a seismic shift for the state government to take. In some ways, it's similar to how New York City's mayor, Bill de Blasio, reversed his position on whether or not he was in support of closing Rikers. What's your analysis of how we got to this point of politicians making this commitment to basically make it so that nine out of 10 cases that were eligible for bail previously are no longer eligible?

sayegh: Community organizing and advocacy. I mean, just, that's it.

WATKINS: You've got to force people.

sayegh: And you have to change the context in which they are making decisions. So, the work that was done on the ground around the state—different coalitions, organizations, a bunch of different groups with a lot of people who had sat in many of these jails, who'd been detained in many of these jails around the state, using their voices, speaking out, educating people, but also creating a political movement that had momentum on the ground in the places that these elected officials lived and worked, from which they obtained their votes.

That organizing has transformed the state dialogue on this to such a degree that when the Republican Senate era ended after the Democrats took over, one of the top priorities when they came in was bail. And the reason that bail was at the top of the reform agenda was because of all this organizing on the ground, and public discussion, and a greater growing public awareness.

But I mean, look, there were rallies practically weekly up in Albany. There were public forums happening around the state, rallies here in the city of New York, protests, op-eds all the time. That kind of political organizing that was happening on the ground is really essential to making stuff like this possible.

WATKINS: It does seem like the criminal justice reform conversation, not just in this state but nationally, is really changing quite rapidly. On the cash bail front, something like nine out of the Democratic presidential candidates, including all the front runners, are on the record as pledging to end cash bail.

Of course, the President's not able to do that, that's another discussion, but, again, you have the work of a lot of activists and groups like Katal behind this movement. How heartened are you by what's happening nationally?

sayegh: It's a completely different world, in many respects, that all these presidential candidates are talking about this. Even four years ago, in the 2016 election cycle, you didn't have it quite like this, and our current president ran on a literal law-and-order platform. We're in a different moment and hopefully it'll continue to build, and we can continue to make the most of it.

A lot of the work that has to be done is on the state level. It's great to hear the federal folks talking about it because it sets a tone, but really the work, if we're going to end mass incarceration, has to happen at the state level. And we actually have to start talking about violence and what we're going to do to divert people and keep people out of prisons for violent felony offenses.

We can't end mass incarceration unless we do that, so that's the next stage probably in the development of the movement, is taking that on in a more robust way.

SFX: music stinger

WATKINS: We have this massive debate going on in New York City right now about closing down Rikers Island, this notorious—and notoriously violent—jail facility. Bail reform, discovery, and the other reforms we've been talking about are going to be important to closing Rikers precisely because they really lower the population further that is going to make closure possible. So, I just want to flag that because these things are connected.

But I want to talk about Rikers a bit now because your group was part of the founding of that movement which launched publicly in April '16, and within a little under a year, led to the mayor pledging to close the facility. Katal stepped down from the campaign in the summer of 2017, but you still very much support the closure of Rikers. The mayor's plan is to replace Rikers with four smaller, modern facilities.

There's a lot of debate about that plan itself. Where is Katal at on the question of after Rikers?

sayegh: When we launched the Close Rikers campaign with JustLeadershipUSA, it was after nine months of work to prep the campaign, and at that time there was not a political consensus around closure. And that was what we had to build and secure, was making something that everyone, where most political leadership in the city and state, said that's impossible, that's not realistic, we can't do that. And we had to transform that dynamic from “that's impossible” to “yes, we're going to do this,” and then go further and talk about how exactly we're going to do it.

The thing that's happening now in our view is that, despite all of the debates and arguments that are happening publicly, there's actually quite a bit of agreement amongst all these actors around a small number of things, at least. There's no question that Rikers needs to get shut down. There's no question that the current jails that we have here in the city—not just on Rikers but the current borough facilities that we have, including a jail boat! People don't know–

WATKINS: Yeah, this floating barge in the Bronx.

sayegh: We have a floating barge called the Boat in the East River. There are hundreds of people detained there. The Brooklyn House of Detention, the Manhattan Tombs—these are horrible facilities with the same culture that they have inside of Rikers, in many respects. And all of these jails should be destroyed and gotten rid of. There's no question about those points. Where there's been a lot of debate that's emerged here is around what to do after Rikers closes down, and here there is a real important split.

The mayor's plan, which we've been working—as has the Close Rikers campaign of which we're a part, and JustLeadershipUSA, and others—to get the mayor to change his plans. So, from the point the mayor introduced that plan in 2017, there's been an effort to get him to change and improve it that is still happening up to this very day. So, the mayor's plan has evolved in response to pressure from groups that have been sustained, working on that.

WATKINS: And that pressure would continue–

sayegh: Exactly.

WATKINS: –even if the plan passes city council.

sayegh: Well, the plan in front of city council, just to be clear, is the land use proposal for these new replacement facilities. That's one aspect, and a critical one, for the mayor's larger plan, but it is not the whole plan. That's important because there are other ways that we've been working to change the mayor's plan, and some real differences that we have. We don't think the Department of Correction should be playing a role managing these facilities in the same way. The mayor's plan is to have them do so. We're fighting that out.

But one of the things we believe is at the center of the debate right now is one of the things that actually doesn't get discussed publicly very much, which is the question of conditions of confinement. And that really is where the debate is revolving around, where the Close Rikers campaign and some of the folks that are arguing for no new jails–

WATKINS: People on the more abolitionist side. In a way we're talking about a debate that's taking place on the left, if we can say that of criminal justice reform…

sayegh: Absolutely. And I would–

WATKINS: …between reformers and abolitionists.

sayegh: I would actually really disagree with that characterization. This is not a debate between reformers and abolitionists, and I say that because Katal is an abolitionist-oriented organization, our aim is abolition. JustLeadership's aim, long-term, at this point is abolition. Other groups that are part of the Close Rikers campaign–

WATKINS: It's how we get there, I guess.

sayegh: It's a strategy question, more than anything. But the reason I highlight this issue with conditions of confinement is: no group has put forward a plan that says that nobody will be detained after Rikers is closed. Every single group has said, we understand that, after Rikers is closed, for the foreseeable future, there will be detention in the city of New York.

WATKINS: That's just a reality.

sayegh: That's a reality. The Close Rikers campaign has put that forward, No New Jails has put that forward, the Lippman Commission, the mayor. The question then is: how many people will be detained then. That's been a huge fight.

We're trying to get the mayor's projection to be much farther down than it is right now. Initially they said 5,000 people, and they've lowered that now to four.

WATKINS: After the bail reform, in part.

sayegh: After the bail reform. We're trying to get them down even farther, and one critical aspect of that is this legislation back up in Albany related to parole reform, because there are 600, 700 people there just on parole violations.

The second thing is: where will these people be detained and under what conditions will they be detained in? Those questions are the fundamental split point between what you're seeing right now happen on the left around how to proceed.

Our position, which we joined with Close Rikers in saying this, is that, since there's going to be people detained here in the city of New York, they should be detained in conditions that are as humane as possible. We should not have people detained in the barge—in the Boat in the East River—in the Tombs, and the Brooklyn House of Detention. If people are going to be detained in the city of New York, they should be detained in conditions that are as humane as they can be.

What the No New Jails folks are saying is: close Rikers and detain the remaining people in the existing facilities. That's the real difference here and where the argument emerges. Now there's different political reasons why people are making that demand, and they wrote a whole plan that you can go read.

For us, the notion that we would keep the barge open is outrageous. It's not a place that should even exist here in the city. We're also a group that long-term is aimed at eliminating detention entirely. How we do that is a question we could spend hours on, and days. It's a huge subject of a fight, longer than what we have [time] for here.

But there will be people detained here in the city of New York when Rikers is shut down. Then the question is: under what conditions will those people be detained, and we believe that, in so far as there's going to be detention here in the city of New York, detaining people in the existing facilities that we have here in the city is inhumane.

And that's the fundamental difference between the two plans. And that's been a lost, in a lot of ways, in the public dialogue and discourse unfortunately, because these are hot, contentious issues.

But yes, there should be a lot of fights and difficult ones about: how is it that we get to a place in this city where people are treated fairly? Where communities are not targeted and criminalized? Where we're not investing and wasting resources and policing in courts and all this other stuff to deal with things that are health issues, and issues about poverty, and housing, and so forth.

WATKINS: So, we have this split on the left right now on criminal justice reform issues about goals and strategies, and what are the current realities. I was struck reading this really great document—that I'll put on the episode page as well—that you did about the Close Rikers campaign, and how it took shape, and organizing lessons to be drawn from it. I was struck by the fact that in the formal launch of the campaign—the sign-on letter—there's no mention made in the letter about what's going to happen after Rikers. The sole focus is on closing Rikers. That clearly was a strategic decision.

sayegh: It was. It was a deliberate and strategic decision because we knew that in order to close Rikers, we were going to need to have all hands on deck. That it was going to require a real robust set of groups all demanding one thing together. And even now, you're seeing the rationale for why we did not articulate what would come afterwards. Because we knew that if we start with where we all agree—everybody can agree or at least we were trying to get people to agree, let's all agree: we can close Rikers.

So, if folks say abolition or bust, folks who are more reform-ended, closing Rikers is what we worked on. We were able to build a consensus within the justice reform community here in the city of New York, that that's a thing that we could all agree on. The moment we start talking about what comes after, you've got a million different ideas.

WATKINS: You got “one no, many yeses.”

sayegh: That's right. That's how we framed it, which is a lesson that came out for us in the global justice movement of the '90s. But here we're seeing now the different perspectives of what to do. If we had started off a Close Rikers campaign with an outline of what was going to come after, it's not clear to me that it would have been successful, or that it would have been successful in the timeline that it was in terms of securing the mayor's commitment.

But the thing is that, once the mayor says we're going to do this, that's when the dynamic shifted. The singular objective was to get the mayor to say we're going to close Rikers—it's going to be the policy to close Rikers. Once that happens, now you have a whole set of other targets you've got to go work on to make it possible: community boards, city council members, tenant associations, block watch groups, church and other faith-based organizations, housing groups, mental health groups.

Our entire city is implicated with the question of “what do we do now,” because to do it you have to fundamentally transform the city. We have to stop using jails as a catch-all for either people that we don't like, or people that we're afraid of, or people who have been lost through the gaps in the social safety net.

What do we do here in the city about the fact that we've institutionalized racial disparities, and that's ingrained, in many respects, in ways that are hard to unroot. Closing Rikers is a fundamentally systems-transformation that is going to be ugly, because that's how that stuff is. And we just knew that if we could have a crystal-clear shared demand of closing Rikers, that we get people on the page for that, that it would put us in a better position to fight out the next phase: how do we do it?

So, fighting to improve the mayor's plan and to get the city, and hold the city accountable here, is a huge factor in all of this at this point. And getting the mayor to follow through, not just on his commitment, but to make the plan align with some of the demands that are coming from communities that have been most impacted by this, has been the work of the last two years, and that's how we got here.

And so, if we're going to get to full closure, in my view it will not come because any elected official says, “I promise you this will happen.” And it won't even necessarily come if we get a legal ruling that says that Rikers has to shut down, because we've seen what happens with those kinds of promises. Or even when we pass legislation, you've got to implement it. If you got a legal ruling, you’ve got to actually do it.

We believe that the closure process is only going to be realized if we sustain organizing and increase that organizing over time until the last person's taken off that island and it's shut down for good. And until that happens, we have to keep up the energy and effort to hold the city accountable on this, regardless of who's in office.

WATKINS: The ugliness that you're talking about, and there's some ugliness on the left right now in this city on the reform stuff.

sayegh: Absolutely.

WATKINS: There's this suggestion coming from the No New Jails side somewhat that anybody who's in favor of closing Rikers—and acknowledges that you're going to need some kind of physical facilities to replace it—that anybody advocating that is some kind of crypto-carceral-stater or something. But it sounds to me like you knew this ugliness was going to come.

sayegh: Yeah, we knew it was going to come. It's a matter of how we organize around it. Some of the demands and claims that are being made, I think there are a lot of passionate folks in this—with social media and whatnot things can be far more amplified. I think if you read the No New Jails platform as we have, and you can see some of the arguments in there are solid, good arguments. A lot of it is really similar to what the Close Rikers campaign has put forward.

And the No New Jails folks themselves have acknowledged that there will be detention afterwards. I don't know what purpose some of the larger vitriol serves other than, that's the kind of vitriol we see that's normalized in today's political climate. So, if you ignore that, and you focus in on the substance here, there's a lot of common ground to build on here.

And if we can find a way for groups, particularly on the left or on the progressive side, to find the areas where there is common ground and collaborate in those places—and to at least where there's disagreement, have those disagreements operate in such a fashion that they don't ultimately disrupt or otherwise pull the rug out from under the larger process—that's usually, I mean, how this stuff goes.

It's not new, it's certainly not intrinsic to this fight. But our larger concern is around the 2021 election cycle here in the city of New York. Whoever's going to be mayor, two-thirds of the city council is turning over, D.A.s are being reelected, borough presidents are being reelected. We're looking at a really seismic shift in the political universe here in the city of New York in the 2021 elections.

And so that's where we think that, wherever we can find common ground with folks along the range of the political spectrum, we should. And then there are some important details, certainly, to disagree around and fight over that we should.

But again, no group, including No New Jails, has put forward a notion that there's not going to be detention, after Rikers closes, for the foreseeable future. And so, we've got to figure out how we're going to proceed there, and do so in a way where we can keep the detention populations on a downward trend as they have been.

And for Katal, and clearly for No New Jails, and I think for folks in the Close Rikers campaign, we eventually want to get to zero. But that's not going to happen until we build more political power. We've got to make additional changes up in Albany, and we're going to have to continue to transform the political dynamics here in the city of New York to make something like that possible. So that's our task.

WATKINS: The work continues, in essence.

sayegh: The work continues.

WATKINS: Well gabriel, thanks so much for your work and for the work of Katal. And thanks so much for making the time to come in here today.

sayegh: Yeah, thanks for having me. I appreciate it.

WATKINS: So, that was my conversation with gabriel sayegh. He is the co-founder and co-executive director of the Katal Center for Health, Equity, and Justice. You heard a couple of references in there to the episode page. It’s full of resources and references to help you dig deeper into today’s conversation: click the link in your show notes or go to courtinnovation.org/newthinking.

For their help preparing this episode, my thanks go to Aubrey Fox, Craig McNair, Sarah Reckess, Tim Donaher, Scott Hechinger, and the illustrious Court Innovation jail reduction duo of Mike Rempel and Krystal Rodriguez.

This episode was edited and produced by me. You can find me on Twitter @didacticmatt and please consider giving New Thinking a rating and review on iTunes. Technical support is from the chary Bill Harkins. Samiha Meah is our director of design. Emma Dayton is our VP of outreach. Our theme music is by Michael Aharon at quivernyc.com. And our show’s founder is Rob Wolf.

This has been New Thinking from the Center for Court Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins. Thanks for listening.