People are not irredeemable. — Ronald Simpson-Bey, JustLeadershipUSA

How will more harm help someone make a change they’re struggling with?

Manhattan D.A. Alvin Bragg talks with New Thinking’s Matt Watkins

“More harm.” That was the focus of a recent two-day training for prosecutors in Manhattan profiled in this episode of New Thinking. Specifically, the “more harm” incarceration inflicts on people; people who have often ended up in the criminal legal system because of harm they’ve experienced.

It’s not the typical message prosecutors receive.

People with lived experience, subject experts, and data were the focus of the training.

Manhattan D.A. Alvin Bragg has set up a new “Pathways to Public Safety” division to reduce the use of incarceration—giving it the same clout as the office’s trial divisions. It will create more alternatives to jail, like treatment and restorative justice, and look for cases across the whole office where they can be used.

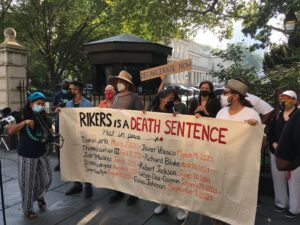

Mounting in-custody deaths add urgency to reducing the use of jail

Adding urgency to this training is the destination for most of the people Manhattan sends to jail: Rikers Island. As the city’s jail population climbs, the facility is sliding ever deeper into chaos and violence. Last year was an historic one for deaths in New York City jails; this year is already worse.

“People want the issues solved,” Bragg says. “We’re not equating safety with incarceration.”

The following is a transcript of the podcast:

Jonathan Giftos: How will more harm help someone make a change they’re struggling with?

Matt WATKINS: Welcome to New Thinking from the Center for Court Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins.

“More harm.” That was the focus of a recent two-day training for prosecutors in Manhattan I sat in on. Specifically, the “more harm” incarceration inflicts on people; people we know have often ended up in the criminal legal system in the first place because of harm they’ve experienced.

Manhattan D.A. Alvin Bragg started the job in January. And he’s been clear he wants to reduce the use of jail and prison. He’s now set up a new team to do that, calling it the “Pathways to Public Safety” division. It will have the same clout as the office’s traditional trial divisions, working to create more alternatives to jail, like treatment and restorative justice, and look for cases across the whole office where alternatives can be used.

But the new division is a gamble.

Bragg announced a series of reforms in a similar vein to this new division when he first took office—promises he’d campaigned on, in part to do with limiting the impact of low-level charges. That was met with a firestorm of criticism in the media and within weeks Bragg had been forced into a partial retreat.

It’s also no small thing to change the culture and practices of a large prosecutors’ office. It’s early in Bragg’s tenure, but there’s no indication in the numbers yet that he’s been able to do much to address the borough’s incarceration problem: per capita, Manhattan continues to send more people to jail in New York City than any other borough.

And being sent to jail in New York City generally means Rikers Island, and that makes this training and this new division even more urgent. As the city’s jail population continues to rise, the Rikers facility is sliding ever deeper into chaos and violence. Last year was an historic one for deaths in New York City jails; this year is already worse.

So, much at stake for a training in alternatives to incarceration, one I think was trying to be more than just a box-checking exercise.

Here, then, is our profile, “Emphasizing the Harms.”

SOUND: Law school classroom buzzing with chatter

WATKINS: It’s a Friday morning at a law school in lower Manhattan but pretty much everyone in this classroom already has a law degree. Many of the Manhattan D.A.’s most senior lawyers are here. Some of the folks attending this training started under legendary Manhattan D.A. Robert Morgenthau. In some cases, that’s long before activists hit upon the idea of the “progressive prosecutor.”

One of the people prosecutors are hearing from today is Marlon Peterson. He starts his presentation by turning around to look behind him.

Marlon PETERSON: Um, it’s interesting (chuckles), it’s interesting… I’m just sitting here looking at the slide behind me and seeing the Manhattan District Attorney Office and just sort of recollecting that the Manhattan District Attorney is the office that prosecuted me many years ago (laughs). Um, and here I’m in a roomful of Manhattan District Attorney prosecutors and to see how my personal experiences are somewhat full circle in being here in this conversation around racial justice some 23 years later, oh my gosh.

WATKINS: At 19, Marlon Peterson was the lookout for a robbery in Manhattan. He was unarmed, but four people were shot during the robbery; two of them died. Peterson spent a decade behind bars.

He remembers how, in the courtroom, the prosecutor liked to refer to everyone accused in the crime as a “Trinidadian posse.” That helped to create a narrative about us, Peterson says. It makes it easier to dispose of people. But we weren’t a “posse,” he says, we weren’t even friends. We were a bunch of 19- and 20-year-olds who got lost trying to drive out of Brooklyn.

He tells the room: think about how you think about people.

PETERSON: This is nuance, the role that you have, even the public defender, the court, the judge, I understand the complexity of it. However, it can never be as complex as the lives of some of these folks. That’s the thing I want to home in on—it can never be as complex as the lives of these folks, because they have to survive it every day.

One thing is that folks, as professionals in the courtroom, you get to leave the courtroom. Of course, you take work home with you, but you do get to leave it. But folks in these communities, they don’t get to leave it. They also don’t get to leave their identities.

When we think about when they are in a place in the justice system once they get in, once they’ve committed harm, we also have to take into consideration that it’s very likely that harm was done to them. And how do you deal with that? That’s a hard question.

WATKINS: How to respond when hurt people, hurt people. It is a hard question, and there’s no one-size answer. What is clear, and people with lived experience of the system have been saying this for pretty much forever, is that the standard responses aren’t working. They’re likely making things worse.

Virginia Barber-Rioja is the co-chief of Mental Health for Correctional Health Services inside New York City’s jails. Here’s what she told the prosecutors she learned.

Virginia BARBER-RIOJA: To me, what I’ve been thinking a lot about since I’ve been working in jails: I’ve really seen first-hand the damage that incarceration causes in people. It’s bad, it’s really bad. For people who are mentally ill, it exacerbates their psychiatric symptoms, it re-traumatizes them. And all of that, as we are learning, it’s what we call a criminogenic risk factor, meaning that actually being incarcerated is a risk factor for rearrest.

WATKINS: The audio wasn’t great there so let me repeat that: being incarcerated is a risk factor for rearrest. The traumas you experience behind bars, and the severing of every relationship you have—from family to employment to treatment—mean you’re more likely to end up back in the system once you’re released than you would have been had you never been incarcerated. It’s not the typical message prosecutors receive in a training. I put that to D.A. Alvin Bragg.

Alvin BRAGG: Right. Well, look, I mean, the people in that room know incarceration and know there are cases and we’re doing them as well. I don’t want to ignore them where incarceration is, we believe that the result, the just result for public safety.

But then there are categories where it’s not, and that’s what we’ve been focused on the last couple of days. Really to make sure this is successful, each case, each human, has to be looked at and paired with the right course—if that’s a treatment alternative, if it’s a non-prosecution alternative.

But the sort of individualized approach, that’s why we’re kind of doing the training so people can know what to look for, can know who the experts to go to internally are, and so that we are making sure that we’re using all the tools in the toolbox because then we’re pulling out the right tool for the right person for the right situation.

WATKINS: One of those tools, a relatively new one, is a Felony ATI court in Manhattan: individualized alternatives to incarceration for people facing more serious charges, the majority of them in fact classed as violent. You might have heard the profile of the court we did last year. Under Bragg’s predecessor, Cy Vance, the Manhattan D.A. was a partner to the court’s creation.

It’s a pioneering approach—many reforms exclude people with more serious charges—and that means the numbers overall are still small. But since Bragg took over in January, the volume of cases the court handles has more than doubled.

Mary WEISGERBER: Well, I would say there is an increasing emphasis on pathways to public safety, on alternatives to incarceration in general…

WATKINS: Mary Weisgerber has been a prosecutor for 17 years. I spoke to her during a break in the training. She’s with the new Pathways to Public Safety division. Prior to that, she was with a trial bureau, prosecuting mostly violent crimes. I asked her: you’re in a two-day training focused mostly on why incarceration isn’t working. What was the attitude to alternatives to jail when you started the job?

WEISGERGER: Initially in my trial bureau there was some thought to that, my bureau chief at the time did put people put into drug treatment programs, but more often we would get a response of, “I have a program in mind for that person, it’s called state prison.” In general, it was not used near as much as it could be.

WATKINS: A question in the background of this training is: even with all of their power inside the system, assuming some prosecutors really want to change business as usual, how much can they accomplish?

By the time many people reach the criminal legal system, Weisgerber points out, multiple systems have already failed them.

WEISGERBER: I think the most frustrating part about it is we still do not have anywhere near the resources we need to do this. And so, as many have said, we are more often pulling bodies out of the river downstream than trying to keep them from falling in in the beginning. And it is so much cheaper to treat people.

There are too many people who think that is soft or crazy-liberal. It’s not! It’s a practical solution to ongoing problems that we have. And until people wake up and start knowing, understanding: you are paying for it one way or another. You’re paying on the frontend or you’re paying on the backend, and when you pay on the backend it is both more expensive, less humane, and less effective. So, we are just making a lot of the same mistakes over and over again and it’s very frustrating.

WATKINS: Making the same mistakes over and over again. Some would argue that’s a decent summing up of decades of policy toward drug use in this country.

GIFTOS: Overdose in New York City is the highest it’s ever been in the city…

WATKINS: Jonathan Giftos used to supervise substance use treatment in New York City jails. He’s an expert on addiction medicine now working with the city’s Department of Health. He leads the prosecutors through a brisk presentation on the harms of drug use, but also on the harms of the approach to drugs taken by the legal system.

It can be five years before someone suffering from addiction seeks treatment, he tells them. And given the likelihood of a return to use, most people engage in multiple rounds of treatment. Then it’s another five years before the risk of returning to use reverts to normal.

GIFTOS: So, you’re looking at like a decade for many people. And the criminal justice system is going to have a really hard time being with someone through this really mountainous course of ups and downs and lefts and rights, because it just takes a long time. I’ve experienced the criminal justice system struggling to like, “what does progress mean, how do I look at this setback?” et cetera.

WATKINS: In other words, the timelines of addiction science and that of the legal system may be irreconcilable.

Giftos highlights a study of so-called “hot spotters” at Rikers Island, the 800 most frequently incarcerated people over a five-year period. Ninety-seven percent of those people had significant drug or alcohol use. That’s almost double the prevalence in the general jail population.

GIFTOS: What this is just showing is that the people who are most frequently incarcerated—very short stays, almost none of them were violent offenses—23 incarcerations. You know, the thinking is: “oh, maybe the twenty-fourth incarceration is going to change something.” Not likely, right.

WATKINS: When drug use becomes risky or problematic, it fuels involvement with the criminal legal system and it can inflict harms: on those who use them and on the people around them. Those harms need to be responded to, and the answers aren’t easy, Giftos says, but they are out there.

First, reduce the harms—he points to the success of overdose prevention sites, places where people can use drugs safely, indoors and receive support and connections to voluntary services. Long a staple in other countries, since they opened a year ago, two new sites in New York City have intervened in more than 500 overdoses—those are lives potentially saved.

Next, treat the trauma—trauma, Giftos explains, triggers risky drug use and that drug use compounds trauma.

And support recovery—abandon, he says, the stigmatizing language of “clean” versus “dirty.” Recovery from problematic substance use is not a linear process. Meet people where they’re at, earn trust, and walk forward together.

Incarceration is the opposite of every item on that list.

Ronald SIMPSON-BEY: It’s a pleasure and an honor to be with you today. And it’s going to be interesting—Sherene gave me coffee… The last time I was in New York, they gave me coffee and a microphone and I talked a dog off a meat truck [laughter].

WATKINS: We’re in a morning session now and Ronald Simpson-Bey walks comfortably at the front of the room with a microphone. You might not think it to look at him, but he has experienced immense trauma. That’s in part what he’s here to tell the prosecutors about.

SIMPSON-BEY: I’m not big on numbers because 27 years was enough numbers for me, so I like to have conversations. I think that conversations provide meaningful pathways forward. The data gives you the foundation, but it’s the stories of lived experience that actually bring meaningful change.

WATKINS: Twenty-seven years. That’s how long Simpson-Bey spent behind bars before his conviction was overturned because of prosecutorial misconduct. He’s now an executive vice president with JustLeadership USA, a reform organization led by the formerly incarcerated.

The desperation inside prisons is real, he tells the prosecutors. Prisons are heaping trauma on top of the already traumatized. You’ve been taught that you have to treat people harshly, he says; you don’t.

SIMPSON-BEY: People are not irredeemable; people deserve second chances. And to give you a perfect example of what I mean, because I always practice what I preach: on Father’s Day 2001, I was sitting in prison in Michigan—I had been in prison for 16 years at the time—waiting on my children to come—I have four children: a son and three daughters.

I talked to my son, “hey dad, I’m going to pick the girls up, we’re coming to see you.” Fantastic—waiting to see my children. One o’clock, two o’clock, three o’clock came. They never show! So now I’m worried, I start making phone calls—couldn’t find anybody, which was strange.

Out of all people, I called my ex-mother-in-law: “hey mom, how you doing?” “Hey, Ronnie.” “Have you seen the kids, they’re supposed to come visit?” She said, “no, you haven’t heard?” I said, “no, what’s going on?” “Little Ronnie’s been shot and killed.”

My 21-year-old son was shot and killed by a 14-year-old juvenile on the streets of Flint, Michigan—on Father’s Day while I was waiting for him to visit. But you know what I did? I forgave that child. Because that child was a victim of the same thing that the people that’s incarcerated, that my son, was a victim of.

So, I forgave that child and I advocated for him to be treated as a juvenile instead of an adult, because in Michigan they were giving life without parole sentences for juveniles convicted of murder. I saw no use in that. It was not going to bring my son back, it was not going to do anything but further er ode the fabric of our community and destroy his family at the same time.

I forgave the child.

WATKINS: In opting for harsh sentences, prosecutors often cite what crime victims want; a recent national survey the Center for Court Innovation helped to conduct found four of five offices saying as much.

But research has found many survivors are like Simpson-Bey. They want the opposite of what the justice system delivers.

Erika SASSON: I try to integrate all of the different perspectives that I have in creating a space for human engagement that is connected, that is alive, that is truthful…

WATKINS: Erika Sasson is working to build that opposite response. A former prosecutor, she studied peacemaking with Indigenous practitioners and now works in restorative justice—“RJ,” as the people doing the work call it. You might recall her from our 2020 episode on restorative and racial justice in schools.

Sasson has worked with the Manhattan D.A. to expand its use of restorative justice: assessing more cases to be sent to community-based providers, bypassing for the most part the court system, and even the prosecutors’ office itself.

The emphasis is on more serious cases, cases that merit what can be an intensive months-long process. And Sasson emphasizes the consent of the victim—or “harmed party,” in the language of restorative justice—is essential.

She tells the prosecutors about a recent case she worked on—an unintentional homicide.

The daughter of the victim wanted to confront the man who had killed her father—confront him as a step towards forgiving him. In the process, he confronted the harm he had caused, and apologized for it.

Everyone should have this chance, the woman said. “I can’t tell you how well I’ve slept since that night. I’m at peace.”

SASSON: And I want to just actually go back to something that this woman said. She said, “everybody should have the opportunity.” This is what I think: I think everybody should have the opportunity.

I wish that 95 percent of your cases went through assessments, essentially, so that they have the opportunity to say, “you know what? I’ve seen the system, I see what you’re offering me, and I still say no.” The fact that we deny people this opportunity to think about whether they might want something different? That for me is the real sweet spot of this work.

WATKINS: On paper, the ambition for restorative justice in Manhattan is clear and substantive. The challenge, as with everything discussed in this training. will be making that ambition a reality.

Sherene Crawford recently returned to the Manhattan D.A.’s Office to head up the new Pathways to Public Safety division.

At the end of Sasson’s presentation on restorative justice, Crawford addresses the room.

Sherene CRAWFORD: I’m not going to lie. What we have here as the guidelines to you: this is a shift in culture for us. We, as an office—I know my experiences as a line ADA and since I’ve been back is—we’re having detailed conversations with victims about what they want to see in the outcome.

It’s going to take us a little time—I don’t expect this to happen tomorrow. I do think this is going to be an adjustment in how we think, in how we approach our work, how we go back to the line assistants throughout the office to talk about this and prepare them for that.

I had a conversation with someone who was very well-intentioned who I admire very much in this office so I don’t mean to tell this story in any other way, but they were like, “I asked them… RJ you can just go in the room and you can yell at the person! And won’t it feel good!” And, I was like, “Ah! That’s not what it is!” But they wanted this person to have their moment, they could feel that they needed something.

We’re not trying to turn 500 prosecutors into RJ experts to explain this to victims and defendants. That’s why we need to turn this over to the folks we’re talking about here to have those conversations.

WATKINS: Along with the emphasis on the harms of incarceration, that’s the other persistent theme of this training: We’re not asking you as prosecutors to be mental health practitioners, addiction medicine specialists, social workers… We are asking you to send more cases to the people that are.

But you can sense some unease in the room at times. Charles Whitt has been with the office for 25 years and currently manages a trial bureau. He’s in charge of about 50 lawyers. In-between sessions, I ask him: how much of what you’re hearing in there is going to change how those lawyers do their jobs?

Charles WHITT: You gotta question. You can’t sit in a room and talk about things on an academic level, and talk about research studies, unless you ask the question: “What does this mean on an everyday level? How do I put this into practice? How is this going to work when I’m talking to assistants who have 150 cases in court every day, are catching hell from the defense bar, getting screamed at by judges, how does this all make sense when they have to talk to families of victims, when they have to decide the right sentencing, when they have to apply Office guidelines?”

That’s where the rubber meets the road in all this sort of academic talk.

WATKINS: Back inside the classroom, at the end of a session on the data that supports moving away from incarceration—a lawyer stands up with an objection. “Perception is reality,” she says, and right now, the public perceives that cities are getting more dangerous. How are we going to make this shift if the public doesn’t support it?

As D.A., Alvin Bragg, a Black man from Harlem, has faced an intensity of opposition from some quarters that is almost unique, even among progressive prosecutors. He’s now contending with a Republican candidate for Governor promising to remove him from office should he be elected.

I asked Bragg: this message about alternatives to incarceration—treatment, restorative justice—is that a hard one to be carrying right now?

BRAGG: It’s interesting. I think in some corners, it’s a challenging message, but I’ll say I spend a lot of time in Manhattan neighborhoods talking to Manhattanites. And I find a lot of encouragement.

People want the issues solved. People do not want crime rates going up. Importantly, we’ve got homicides and shootings going down in Manhattan, but we’ve got a lot of other things trending the other direction, and people are noticing that and they’re concerned, as they should be deeply concerned about public safety.

But when we talk about this with Manhattanites in some of the areas that have the most kind of significant, I would say mental health issues, homelessness issues, which people are bringing to my attention. And when those become issues as they do sometimes that fall into the criminal arena, when we’ve engaged with them, we’ve talked about Pathways. And there’s an openness.

I said, “Look, we want to solve the problem. We want to be safe. We’re not equating safety with incarceration.” Now, the challenge is is that’s usually a conversation. It takes a back-and-forth when you have a bullet point or a news headline, a tweet, the sort of shorter forms of communication that we have, I don’t think we get to that level of granularity and nuance.

WATKINS: Prosecutors have a lot of discretion, and discretion means power. That’s the insight at the origin of the progressive prosecutor movement: what if that power was used to shrink, not compound, the harms of the system?

But with discretion comes an absence of guidelines. Do prosecutors have any professional duty to divert more cases away from jail, to offer ATIs, alternatives to incarceration? Or, for now, are we more in the realm of ethics: what’s owed to the people prosecutors encounter, what’s owed to justice?

That was focus of the presentation by Julian Adler, the director of innovation and strategy at the Center for Court Innovation. He helped to put together this training.

Make ethics your guide, Adler urges the room, and root those ethics in relationships.

VIDEO CLIP: [sound: baby cries out] Narrator: In the Still Face experiment what the mother did is she sits down and she’s playing with her baby who’s about a year of age. [sound: cooing noises from mother]

WATKINS: Adler shows the prosecutors a video of what’s called the “still face” experiment: a mother interacts energetically with her baby, face-to-face—responding verbally, playing with her, turning to look at where her baby points—but then suddenly, brutally, she stops. The mother’s face becomes impassive, neutral. She makes no response to the baby’s cues. The baby goes from cajoling to frustrated and then quickly to a state approaching panic. It’s heartbreaking to watch.

Adler tells the prosecutors: by the time people reach the criminal justice system, they need a human response; they need something more than impassivity.

Julian ADLER: My argument for a lot of the folks that you’re considering, or not considering, for ATI are waiting for that surround of love and support to begin to thrive, for the brain to rewire, and to live different lives. Now I’m not suggesting, I know: you’re not doing therapy, but you’re a part of the environment that’s going to determine how this person encounters the world at this juncture.

All approaches to helping people who have been hurt turn on relationship and resetting relational dynamics. So my argument for you, my parting words are: as you begin to think about what makes an action ethical, it’s not that every case is going to be appropriate, but to think relationally about your ethics. Since your goal is behavior change, and the way to behavior change is relationship. And that’s as rigorous and scientific—the only science I can give you to hang your hat on, it’s this. So, orient your ethics to relationships. It’s a tool, and it’s a powerful one.

WATKINS: That was our profile, “Emphasizing the Harms.” For more information about this episode, and all of our episodes, go to courtinnovation.org/newthinking. Indeed, if you enjoyed this episode, you might want to scroll back in your feed to 2018 to hear the series we did on the then-emerging progressive prosecutor movement. There are interviews there with the likes of Kim Foxx, Marilyn Mosby, Emily Bazelon, and Larry Krasner.

For their help with today’s episode, my thanks to John Wolfstaetter and the entire audio-visual team at the District Attorney of New York; also to Tia Pooler, Joe Barrett, Dave Lucas, Sherene Crawford, and Julian Adler.

This episode was produced and edited by me. Emma Dayton is our V-P of outreach. Samiha Amin Meah is our photographer and director of design. Our theme music is by Michael Aharon at quivernyc.com, and our show’s founder is Rob Wolf. This has been New Thinking from the Center for Court Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins. Thanks for listening.