Amy Pumo is the director of the Child and Adolescent Witness Support Program located in the Bronx District Attorney’s Office. She has a background in psychology and social work with a specialization in trauma. She spoke with Carolyn Turgeon about the project.

What is the purpose of your program?

The program’s aim is to assist children and teenagers ages 3 to 15 in overcoming the negative impact of violent crime. They’re all victims or witnesses of a violent crime—that includes children who witness homicides of loved ones, children who are sexually or physically abused, and youth who witness domestic violence or are in intimate partner relationships that involve violence.

We provide crisis intervention, support through the criminal justice process, and ongoing therapy to assist them with processing the experience, helping them to put the traumatic event in the context of their lives and see it as a part of who they are but not have it define who they are, and in this way we help them to begin to heal.

How do you work with the children?

The children and teens who enroll in therapy often receive a combination of individual sessions, sibling sessions, parent/child sessions and family sessions. We also offer group therapy. I think maybe what’s unique is our focus on families. We don’t just treat the children. We believe in a strong collaboration with parents and the rest of the family system to help the child overcome the experience. The parent has to be involved from the beginning, not only consenting to the therapy but becoming an integral part of the therapeutic process. During the child’s enrollment process we talk with the parents about the importance of their involvement and help them assess whether they’re able to make that kind of commitment.

Have you been successful in getting referrals?

Absolutely. We’ve had almost 600 referrals since the program started three and a half years ago, so there’s no lack of child victims who need services. The referrals come primarily from crime victim advocates and prosecutors. And then there’s a small percentage that come from local hospitals or Family Court or police.

Can you tell us, without violating confidentiality, about a client?

Well I’m working with two siblings right now who witnessed the homicide of their mother. They receive a combination of individual therapy, sibling therapy, and parent/child therapy with their grandmother who’s their primary caretaker. These children were present when their mother’s boyfriend murdered her. We use a combination of play therapy and art therapy and traditional talk therapy, mostly coming from a cognitive behavioral perspective within the context of trauma. We also incorporate elements of narrative therapy.

Can you explain a bit more about these different kinds of therapy? How do they work?

Well when children have had an experience like this, one of their ways of working through it can be by repeating the story and trying to make sense of it, and trying to create alternative outcomes, at least in the way that they experience the event, to help them move from a place of feeling helpless and powerless to a place of feeling like they have some control. So in play therapy they create stories with toys or objects. They may not be directly recreating the exact traumatic story; for example, if it’s a case of sex abuse they might not have a story about a child who gets sexually abused by their uncle in their play, but they’ll have a story about kids going down a slide that they think is going to be fun but in the end is actually a trick by a mean man who hurts them when they get to the bottom of the slide. They use metaphor, unconsciously, of course, and in the play the therapist engages them in those stories and looks for themes of resilience and encourages such themes, encourages ways that the children in the stories can seek out help or figure out what they can do to feel safe again. We also help them correct cognitive distortions that can lead to unhealthy symptoms, like thinking it’s their fault. If in the play the child creates the idea that the kids going down the slide are supposed to know that there is something dangerous at the end of the slide, it’s important to help them to realize that they couldn’t have known, that it’s not the children’s fault, but the fault of the person who is hurting them.

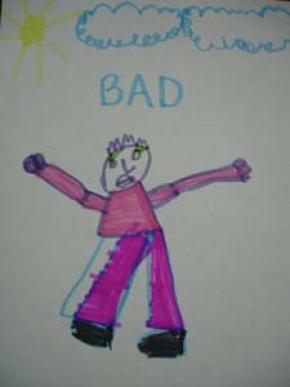

So that’s how it works in play, and it’s quite similar in art therapy. The children create images that have meaning to them and so the therapist helps them engage with what they’ve created and pull out the meaning of it and then use that as a way to foster healing.

Can you give an example?

Well one example was a little girl, about five years old, who had been sexually abused by a stranger. In her first month and a half of therapy, every time she did a drawing of herself and the abuser she drew them close to each other on the page; she made these big drawings of herself saying “no” and him saying “come here” and she repeated this again and again. Like I mentioned, there’s this need to make sense of what’s happened. Then we had this play experience when she initiated a reversal in the roles, to where I was going to be the sexually abused child and she was going to be the therapist. And in the play I said to her as the child “I’m scared, what can I do?” and then as the therapist she was able to talk about the resources available to me: going to Mom, calling for help, and things like that. So she stepped into the position of power, and maybe a week or so after that play experience in her art she still had herself as the child and the abuser was still in the picture but instead of being front and center in the image they were much smaller. The abuser was further away from her on the page; she was all the way at the top of the page and she very deliberately showed how far away they were from each other, indicating each step that she had run from him. The immediacy of the threat had changed, she had taken initiative to escape, and in addition to that she had added another little girl with her in the drawing, standing next to the girl who had represented her in the previous images. The additional little girl was the sexually abused child I had played in our role reversal. So now she was feeling less alone, more in control, and there was distance from the danger evident in the drawing that she created. So she as a five-year-old wouldn’t be able to consciously verbalize all this but was able to do it from a non-verbal place of creating images.

How long do you work with a child like that or does it just depend on their rate of healing?

Yes, it just depends on their symptoms, if there’s been a decrease or an increase. It’s a joint, collaborative decision between the child, the parent, and the therapist based on improvement. But going forward we’re going to be using a standardized instrument to assess symptoms and use that as a guide. At this point there are some children who’ve been in the program two years, and when they get to that point they’re not necessarily coming every week, but having maybe once-a-month contact. And then there are kids who are here for a year and finish, and then a year and a half later we get a call from Mom that there are some other problems emerging, which is very typical when you experience a trauma. You process it and heal from it to the extent that you can at that age, and then when developmental changes occur, and you go through different phases of your life—and this is true through adulthood—sometimes you need to go back to the experience and work on healing it now from that perspective. The experience is never forgotten but you create places of acceptance and develop the ability to move beyond it.

What are your other plans for the future of the program?

The plan for the future is to create more groups. We have a support group right now for teenage females who were sexually abused, but because there are a lot of children who are witnesses to homicide we want to create groups around that, groups that are ongoing, that have cycles of 10 to 12 weeks and then start up again after a break, so we can reach more children that way. And hopefully at some point we can hire another full-time staff therapist. We’re also looking at ways to enhance what the families are receiving outside of just traditional therapy. We want to look at ways to better connect families to their natural resources in the community.

What advice you would give to people in the criminal justice system who work with children and don’t have this kind of program available?

I would say that it’s important to really help build the resources within the family of the child who’s been the victim. To not just have that individualized focus on the child but to have a family focus because the family will be the child’s support for the rest of his or her life. Those are the meaningful relationships where healing can really occur.

Also, it’s important to make sure that children are referred not only to therapy but to other programs that create opportunities for fun, for self-esteem building, for leadership building and for enhancing their sense of connection to their community.

In terms of the therapy, I think it’s important to remember that it’s not only the trauma but the events surrounding the trauma that have a strong impact on the children. For example, take a child who’s sexually abused by her mother’s boyfriend and then, if the mother doesn’t do what she needs to do to protect the child, is removed and put in foster care. For that child, being removed from Mom can be just as significant to the child as the abuse. So you need to look at the full spectrum of what’s occurred because of the event, and not just focus on the event itself.

Another big recommendation would be to understand that the work of trauma healing can occur without strictly focusing on direct processing of the actual event. Not every child has to repeat the story of what happened in great detail. Doing things like restoring a sense of safety, restoring a sense of personal autonomy, of efficacy, of personal power—these are equally powerful ways to assist kids with healing from the trauma without having to rehash the details of what happened. However, the child should always be offered the opportunity to rehash the details if they feel ready and want to.

Another thing: before delving into the elements of traumatic experiences, the details of what happened, it’s helpful to build the children’s coping skills and resources so that they can return to the experience of the trauma from a place of greater strength, so that it doesn’t become re-traumatizing to them.

It’s also helpful to pay attention to the way the trauma impacts the children’s ability to regulate their physiological arousal. It’s important to incorporate elements of body work, things like deep breathing or yoga, into the therapy, as ways of calming the hyper-aroused energy that can reside in the body after these types of experiences. It’s about respecting the mind-body connection.

And then there’s one last thing that is crucial, if you’re doing this work with children: to be able to honor the complexity of the experience for the child. Most of the time this violence is intra-familial. The children have personal, intimate relationships with the people who are perpetrating the crimes. So it’s really important for them to have the space for holding contradictory emotions. For example, it’s vital for the children whose father murders their mother to be able to talk about how much they hate what he did and how angry they feel with him, but at the same time be able to talk about how much they miss their father who is now incarcerated and what they used to love doing with him.

June 2007